The Relationship between R2P and the WPS Agenda: Addressing the Gender Dimensions of Atrocity Prevention

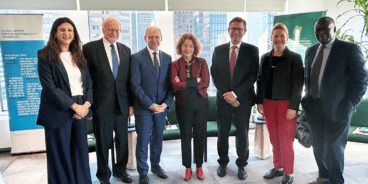

The following keynote address was delivered by the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict, Ms. Pramila Patten, at the Annual Evans-Sahnoun Lecture on the Responsibility to Protect, co-hosted by the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations and the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect on 23 May 2022.

Excellencies, Ladies and gentlemen, good morning.

It is an honor to be here to deliver the 12th Evans-Sahnoun Lecture on the Responsibility to Protect. I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to Ireland for hosting this event, and in particular to Her Excellency Ambassador Byrne Nason, our “Ambassador of conscience” at the United Nations, and a steadfast champion of civilian protection and the Women, Peace and Security agenda, notably during Ireland’s exemplary tenure on the Security Council. Thank you also to Executive Director Pawnday, of the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, for your leadership, and to The Honorable Gareth Evans for your pioneering and continued contribution to the development of this doctrine.

We meet at a moment of great global turbulence, marked by multiple, cascading crises, including an epidemic of coups and military takeovers, from Afghanistan, to Guinea, Mali, Myanmar, and elsewhere, which have turned back the clock on women’s rights. Even as the world contends with recovery from a multi-year pandemic, and its social and economic aftershocks, we are confronted with the highest levels of conflict since the creation of the United Nations, and with record numbers of people forced to flee their homes and homelands, due to violence and persecution. In this climate of extreme uncertainty, it is not hyperbole to ask whether international law is an empty promise; whether our collective responsibility to protect is more honored in the breach than the observance; and whether the ten Security Council resolutions on Women, Peace and Security are making a tangible difference for women whose lives have been engulfed by war.

When States came together for the 2005 World Summit, at which they unanimously endorsed the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity, the international community was reeling from atrocities in the Balkans and Rwanda, which had shocked the conscience of humanity. Indeed, then Secretary-General Kofi Annan told the gathering, in no uncertain terms: “You will be forced to act if another Rwanda looms”. A similar impetus and manifestation of political will, in response to widespread and systematic sexual violence, notably in Darfur and Eastern DRC, led to the creation of my mandate by the United Nations Security Council in 2009. The atrocity crime of conflict-related sexual violence has been called “history’s greatest silence”, and remains one of the most frequently committed, yet least condemned crimes of war. Indeed, every new wave of warfare brings with it a rising tide of sexual violence. The ancient trilogy of wartime terror – looting, pillage, and rape – which should long ago have been consigned to the history books, remains in our daily headlines.

Let us be clear: Unpunished crime is repeated crime. It is starkly evident across the warzones of the world that lawlessness is tantamount to “license to rape”. Accordingly, the central challenge of my mandate is to convert the vicious cycle of violence, impunity, and revenge into a virtuous cycle of reporting, resourcing, and response, including in terms of protection, assistance, and accountability.

Conflict-related sexual violence is not explicitly mentioned in the R2P doctrine, but it is recognized in the definition of the relevant crimes under international law. In 2008, the Security Council adopted the breakthrough resolution 1820, which elevated this issue squarely onto its agenda, recognizing that sexual violence can constitute a war crime, a crime against humanity, and/or a constituent act of genocide, depending on the facts of the case. This ushered in a historic shift in paradigm and perspective, from sidelining sexual violence merely as the “random acts of a few renegade soldiers”, an “inevitable byproduct of war”, or form of “collateral damage”, to addressing it with greater alacrity as a self-standing threat to collective security and an impediment to the restoration of peace. This sent a clear signal that sexual violence – even in the midst of war – is preventable, not inevitable. It recognized that sexual violence is used and commissioned as a tactic of war to humiliate, dominate, terrorize, disperse, and forcibly displace members of a targeted community or ethnic group, shredding the social fabric that binds people together, with corrosive effects on social cohesion.

Over 15 years since R2P was endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly, and almost 15 years since the inception of the Security Council agenda to combat conflict-related sexual violence, progress can be assessed in three key respects, namely in terms of: normative evolution, institutional capacity, and operational impact. There are some striking and instructive parallels between the trajectories of these two agendas.

Firstly, the normative force of the R2P doctrine has been widely felt in international relations, and global standards have been set, and become well-established, notably of sovereignty reconceived as responsibility, primarily to citizens, but also to the international community writ large. The doctrine has been invoked in numerous Security Council resolutions since 2006, and has influenced innovations such as the responsibility of permanent members of the Council to refrain from using the veto when confronted with atrocity crimes. Likewise, successive Security Council resolutions have made it clear that, as a crime of concern to the international community as a whole, sexual violence must be addressed in transitional justice processes, and excluded from the scope of amnesty provisions. Both agendas remind us that the normative framework is robust: what is needed now, is not new standards of behavior, but better adherence to those that exist.

Secondly, in terms of institutional arrangements, R2P has catalyzed more organized and structured attention to atrocity prevention across the United Nations system, spearheaded by the Office on the Prevention of Genocide and the Responsibility to Protect, and through the Global Network of R2P Focal Points. Similarly, the United Nations is today equipped, as never before, with the infrastructure to prevent and respond to the historically hidden crime of conflict-related sexual violence, under the strategic leadership of my mandate. This includes the multisectoral, interagency coordination network that I Chair, known as UN Action Against Sexual Violence in Conflict; a Team of Experts on the Rule of Law and Sexual Violence in Conflict, which aims to strengthen institutional safeguards against impunity for these crimes at the national level; and through Women’s Protection Advisers (or WPAs) who are deployed to the field to enhance our monitoring, reporting, and response, as an evidence-base for advocacy and action.

Turning to the vexed, but critical, question of operational impact: I would note that both agendas are, first and foremost, prevention agendas, which aim to reduce the risk of atrocity crimes before they occur, including by ending the culture of impunity that fuels violations, and emboldens their authors. In both agendas, we are at an inflection point: How can we translate commitments into compliance, and resolutions into results? How can our collective responsibility yield a real-time collective response? The normative frameworks and institutional arrangements exist for rapid and coordinated action to react swiftly to imminent abuses, incitement, and hate speech, before nations and peoples are plunged into crisis.

On a positive note, there is no doubt that the United Nations system is today reaching and supporting thousands of survivors of wartime sexual violence, who had once been invisible and inaccessible. Peacekeepers are now systematically trained to detect, deter, and respond to sexual violence as part of their operational readiness standards to protect civilians. The mandate authorizations and renewals of peacekeeping and special political missions include directives on sexual violence prevention and response. Specific designation criteria on sexual violence have been included in 8 of the 14 United Nations sanctions regimes, which I brief on a regular basis, as part of leveraging behavioral change, and opening space for a protection dialogue with belligerent parties, backed by the credible threat of enforcement measures. Dedicated experts on sexual and gender-based violence are routinely deployed to international monitoring and investigative mechanisms, and there is an ever-growing cadre of specialists in this field. The operational arms of my mandate are delivering concrete projects on the ground to support survivors, funded through our dedicated CRSV Multi-Partner Trust Fund.

We also have on the public historical record, 13 annual Reports of the Secretary-General on Conflict-Related Sexual Violence, which not only document incidents, patterns, and trends of sexual violence employed as a tactic of war, torture, terrorism, reprisal, and political repression, but also lists or “names and shames” the parties responsible, including both State and non-State actors. Furthermore, the Secretary-General has, also since 2009, published annual reports on the responsibility to protect, which have explored various dimensions of the issue, including in 2020, the nexus with the Women, Peace and Security agenda. This report noted the need to deepen understanding of the gendered drivers and dynamics of atrocity crimes, in order to help States, regional organizations, and other actors more effectively and holistically discharge their responsibility to protect.

When taking stock of our operational impact, it is important to observe that we have avoided the politicization of my mandate, and its instrumentalization for political ends. Through a rigorous data-collection methodology and disciplined reporting practice, we have insulated this agenda from political machinations that could paralyze, sensationalize, or discredit our work –given the history of wartime rape has been a history of denial.

As part of our operational methodology, which focuses on anchoring commitments at the national level, my Office has signed a dozen Joint Communiqués and Frameworks of Commitment to prevent and address conflict-related sexual violence, with almost all of the countries that fall within my remit. This aligns closely with the pillar of R2P focused on assisting States to bolster their domestic capacity to protect. As the United Nations, we can support, but can never supplant, the primary responsibility of States to protect their populations.

Earlier this month, I visited Ukraine to sign a Framework of Cooperation with the Government on behalf of the United Nations system on the prevention and response to conflict-related sexual violence. This framework includes measures to strengthen national Rule of Law and accountability systems, and to facilitate evidence-gathering to support eventual prosecutions. Since the 24th of February, I have repeatedly called for swift and rigorous investigations to ensure accountability as a critical pillar of prevention, deterrence, and non-repetition. The failure to acknowledge and address atrocities is the surest sign that they will continue unabated.

We are here today in Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, named for the second United Nations Secretary-General, who famously said, half a century ago, that the UN was not “created in order to bring us to heaven, but in order to save us from hell”. Ukraine, right now, is a hellscape in the heart of Europe, and the clearest illustration that, even by this modest standard, we have failed to prevent the suffering of civilians.

As Secretary-General Guterres has stated: “When we talk about war crimes, we cannot forget that the worst of crimes is war itself”. What I witnessed recently in Kyiv – where conflict had, almost overnight, turned cities into crime scenes – makes it abundantly clear that no amount of protection or assistance is a substitute for peace. The aim of my mandate, and that of the wider Women, Peace and Security agenda, is not simply a war without rape, but a world without war.

It is a critical insight of the R2P doctrine that prevention is the best protection. Our latest annual report on conflict-related sexual violence focused on enhancing structural and operational prevention, and made five key recommendations to chart the way forward:

- Firstly, concerted diplomatic action upstream to ensure that sexual violence is addressed in ceasefire and peace agreements, recognizing that no agreement can be comprehensive if the gunfire ceases, but the weapon of rape continues unchecked.

- Secondly, using early-warning indicators of sexual violence to inform monitoring, risk assessments, and early response.

- Third, leveraging the credible threat of sanctions to curtail the flow of arms and resources to perpetrators and spoilers to the peace, to incentivize corrective action and compliance with international norms. Targeted and graduated measures for atrocity crimes, such as sexual violence, including asset freezes and forfeitures, visa denials, and travel bans, raise the perceived “cost” of war’s so-called “cheapest weapon”.

- Fourth, gender-responsive justice and security sector reform, including the vetting, training, and oversight of security sector institutions, and gender balance among their personnel, to ensure they are equally accessible and responsive to women. For instance, the presence of female police officers is consistently found to correlate with an increased willingness on the part of survivors to report sexual violence.

- And fifth, amplifying the voices of survivors and affected communities in decision-making processes, to ensure that local realities guide the global search for solutions. In this respect, we must defend women’s human rights defenders, and protect the protectors, who are often the first responders on the frontlines. It is critical to safeguard civic space, which is shrinking – if not closing – in many settings. The safety of victims and witnesses who bravely come forward to testify must be guaranteed, as well as that of journalists who risk their lives to share these stories with the world.

In short, we must bring all political, diplomatic, humanitarian, economic, coercive, and non-coercive tools to bear to avert atrocities. In this regard, the aims of my mandate, and that of R2P, are mutually-reinforcing.

Excellencies, Colleagues,

The bandwidth of our international community is limited, but even as the eyes of the world are fixated on the horrors unfolding in Ukraine, we cannot avert our gaze from other entrenched conflicts, where the needs of survivors and populations at risk remain unmet. From Yemen, to Tigray, from South Sudan, to Darfur, Syria, Mali, Myanmar, the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, to the Central African Republic where cases of conflict-related sexual violence doubled last year – nowhere is the level of political resolve and resources equal to the scale of the challenge.

In a tragic inversion of the call to turn our proverbial “swords into ploughshares”, we are instead witnessing Ukrainian wheatfields being turned into battlefields, with famine looming in many parts of the world. As always, those who are most marginalized, and furthest behind in terms of health, wealth, and education, will be hardest hit. At this moment, several States are making deep cuts to their Official Development Assistance (ODA), even though sustainable and inclusive development is the surest way to prevent conflict and preserve peace. We must recognize that there is no other way to close the protection gap, than by first closing the funding gap. And yet, both gaps continue to grow. We need to bring the full repertoire of skills and perspectives to bear in confronting the challenges of our time. We know that local women are often the first to raise the red flag about rising extremism and radicalization; hate speech; the accumulation of small arms and light weapons; and the mobilization and recruitment strategies of armed groups; and yet, they are the last to be heard and heeded by security stakeholders. Security policy is still a male-dominated domain, despite clear and compelling evidence linking gender equality and women’s participation with durable peace.

Living through a global pandemic has been a poignant reminder of our fragility and interdependence. We must seize this moment to strengthen global solidarity. It is time for unity to replace impunity. Impunity acts like a virus, infecting both individual bodies, and the body politic; spreading rapidly through communities, peoples, and power structures. There is no vaccine for toxic masculinity, misogyny, patriarchy, autocracy, or gender apartheid. Even if we could prevent atrocity crimes, protection gains will not be sustainable in the absence of equality, empowerment, accountability, and the Rule of Law.

Building back better means forging a new social contract in which no military or political leader is above the law, and no woman or girl is beneath the scope of its protection. It means silencing the guns, and “unmuting” the voices of women. We cannot stand by as atrocity crimes are obscured beneath the “fog of war”, or glorified through medals and monuments that make a mockery of the rules-based international order. Peace is not a passive state; it must be proactively waged, because what is at stake for all of us is the quiet miracle of an ordinary life, a life free from violence.

To conclude, I would urge each one of us to reflect on what we will make of this moment. Will the injunction of “never again” continue to ring hollow? Will humanitarian action and civilian protection go down in the history of ideas as a long litany of “too little, too late”? Or is international law, and the multilateral system, more relevant and urgently needed now, than ever?

In these uncertain times, I believe that doubt is justified, but despair is not. As a Ukrainian woman civil society activist put it: “We must do everything possible, and everything impossible, to end abuses and atrocities”. This is an important reminder to not just do what is easy, but what is necessary, and what is right. Process is not progress. Norms have no power unless they are respected, implemented, and enforced. If we are to truly meet our responsibility to protect, then none of us can rest until every woman and girl, every innocent civilian, can sleep under the cover of justice.

Thank you.