The UN, Rwanda and the ‘Genocide Fax’ — 20 Years Later

On 21 January 2014 Global Centre for R2P Executive Director Simon Adams published the following op-ed in HuffingtonPost.

Twenty years ago on 11 January 1994 General Roméo Dallaire sent his now infamous “Genocide Fax” to United Nations headquarters in New York. At the time Dallaire was Force Commander of the UN peacekeeping mission for Rwanda, UNAMIR. Three months before a horrifying genocide that would claim nearly a million lives in just 100 days, Dallaire discovered that ethnic Hutu extremists were distributing stockpiled arms to Interahamwe militias. A high-level informant had also revealed to him that, as Dallaire wrote in his fax, “he has been ordered to register all Tutsi in Kigali” in preparation “for their extermination.”

In January 1994 Kigali was a dangerous and deadly city. Anti-Tutsi hate speech was being broadcast on the radio. A civil war had led to a formal peace agreement, which UNAMIR was supposed to police, but it was already fraying as future genocidaires drove their country to the abyss. President Juvénal Habyarimana appeared unwilling and unable to confront Hutu extremists within his own government.

Weighing the evidence, Dallaire came to the conclusion that coordinated raids on these arms caches by UNAMIR could prevent a potential mass slaughter. His fax informed UN headquarters that while such an operation was not without serious risk, and could be a deadly trap, it was necessary to act. The final line, the only one written in his native French, read: Peux ce que veux. Allon-y. (Where there is a will there is a way. Let’s go.)

The response from New York was shockingly dismissive. The then-Head of UN Peacekeeping Operations, Kofi Annan, ordered that no arms cache raids take place and instructed Dallaire to strictly adhere to his mandate. Later instructions from headquarters warned against “unanticipated repercussions” that could result from taking action to prevent the tragedy that was slowly unfolding before Dallaire’s eyes. In New York there was neither the will, nor the way.

On the night of 6 April 1994 President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down and the genocide began. The weapons UNAMIR was forbidden from seizing were among those used against innocent civilians as execution lists were activated. Although the UN Security Council crippled UNAMIR, Dallaire and his troops stayed throughout the carnage. UNAMIR protected and saved an estimated 30,000 Rwandans, but Dallaire and his men could not stop the genocide.

Former U.S. Ambassador David Scheffer, who served under President Clinton during the Rwandan genocide, has pointed out that where mass atrocities are concerned, all too often “the costs of not acting are ignored while the easier task of highlighting the risks of acting dominate the discussions.” After Rwanda the UN learned the painful lesson that its impartiality could be manipulated and become an excuse for inaction and indifference to evil.

On this grim anniversary we should derive some solace from the fact that much has changed since 1994. For example, in 2005 UN member states unanimously accepted that they have a collective “Responsibility to Protect” those threatened by genocide and other mass atrocity crimes.

We see today much greater awareness that mass atrocities diminish us all as human beings. Using a range of preventive tools and where necessary, coercive measures, the international community has upheld its responsibility to protect in Libya, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and elsewhere. Since last December, we have seen the UN rapidly mobilize to protect civilians in South Sudan and Central African Republic from ethnic or inter-religious violence. These are positive developments.

While the UN Security Council has been unforgivably ineffective in halting mass atrocities in Syria, this has not stopped the international community from imposing sanctions and cutting diplomatic ties with Damascus. Unlike Rwanda in 1994, the UN General Assembly has spoken out and called upon the Security Council to live up to its responsibilities. But more must be done.

Raphael Lemkin, the Polish Jewish refugee from the Nazis who authored the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention of Genocide, once said that his political goal in life was to “shorten the distance between the heart and the deed.”

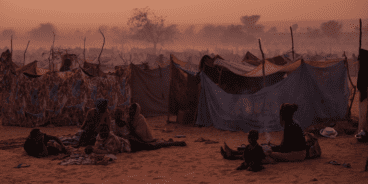

Even with political commitment from the UN, operational under-resourcing can still doom a civilian protection mission. Right now in the Central Africa Republic, French and African Union troops are struggling to save civilians marked for death because of their religious affiliation. While the UN Security Council continues to debate the timing and cost of a transition to a formal UN peacekeeping mission, the current intervention force is unable to stem the bloodletting. More troops and more help are desperately needed.

We are often told that diplomacy requires patience. “‘Patience’ is a good word when one expects an appointment, a budgetary allocation, or the building of a road,” wrote Lemkin in 1942 during the Holocaust. “But when the rope is already around the neck of the victim and strangulation is imminent, isn’t the word ‘patience’ an insult to reason and nature?”

Even where there is a will, the UN sometimes still struggles to find a way.

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 435: Sudan, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Democratic Republic of the Congo