Sudan: Urgently convene a special session and establish an investigative mechanism

To Permanent Representatives of Member and Observer States of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (Geneva, Switzerland)

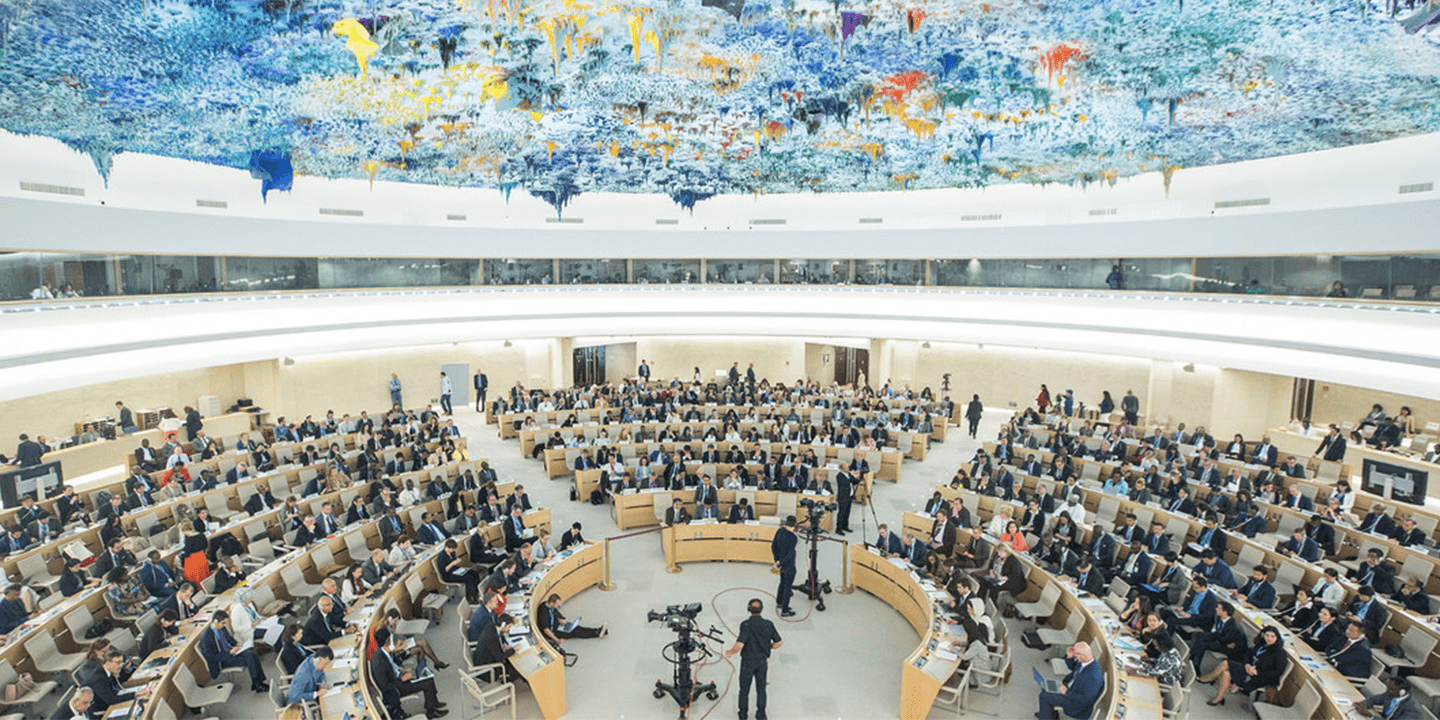

Excellencies, In light of the unfolding human rights crisis in Sudan, and notwithstanding efforts to stop the fighting by the African Union (AU), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and other regional and international actors, we, the undersigned non-governmental organisations, are writing to urge your delegation to address the human rights dimensions of the crisis by supporting the convening of a special session of the UN Human Rights Council.

In line with the Council’s mandate to prevent violations and to respond promptly to human rights emergencies, States have a responsibility to act by convening a special session and establishing an investigative and accountability mechanism addressing all alleged human rights violations and abuses in Sudan.

We urge your delegation to support the adoption of a resolution that requests the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to urgently organize an independent mechanism to investigate human rights violations and advance accountability in Sudan, whose work would complement the work of the designated Expert on Sudan.

* * *

On 15 April 2023, explosions and gunfire were heard as violence erupted in Khartoum and other Sudanese cities between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) led by Sudan’s current head of state as Chairperson of the Sovereign Council (SC), General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan, and a paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (also known as “Hemedti”).

As of 25 April 2023, at midnight, a 72-hour ceasefire has been announced. The death toll, however, is estimated at over 400 civilians, with thousands injured. Actual figures are likely to be much higher as most of Khartoum’s hospitals have been forced to close and civilians injured during the crossfire cannot be rescued. Millions of residents are trapped in their homes, running out of water, food and medical supplies as electricity is cut and violence is raging in the streets of Khartoum. Banks have been closed and mobile money services severely restricted, which limits access to cash, including salary and remittances. Diplomats and humanitarians have been attacked. The fighting has spread to other cities and regions, including Darfur, threatening to escalate into full-blown conflict.

In a Communiqué, the AU Peace and Security Council noted “with grave concern and alarm the deadly clashes […], which have reached a dangerous level and could escalate into a full-blown conflict,” “strongly condemned the ongoing armed confrontation” and called for “an immediate ceasefire by the two parties without conditions, in the supreme interest of Sudan and its people in order to avoid further bloodshed and harm to […] civilians.”

* * *

In light of these developments, we urge your delegation to support the adoption, during a special session on the unfolding human rights crisis in Sudan, of a resolution that, among other actions:

-

-

- Requests the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to urgently organize on the most expeditious basis possible an independent investigative mechanism, comprising three existing international and regional human rights experts, for a period of one year, renewable as necessary, and complementing, consolidating and building upon the work of the designated Expert on Human Rights in the Sudan and the country office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, with the following mandate:

- To undertake a thorough investigation into alleged violations and abuses of international human rights law and violations of international humanitarian law and related crimes committed by all parties in Sudan since 25 October 2021, including on their possible gender dimensions, their extent, and whether they may constitute international crimes, with a view to preventing a further deterioration of the human rights situation;

- To establish the facts, circumstances and root causes of any such violations and abuses, to collect, consolidate, analyze and preserve documentation and evidence, and to identify, where possible, those individuals and entities responsible;

- To make such information accessible and usable in support of ongoing and future accountability efforts, and to formulate recommendations on steps to be taken to guarantee that the authors of these violations and abuses are held accountable for their acts and to end the cycle of impunity in Sudan;

- To provide guidance on justice, including criminal accountability, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence;

- To integrate a gender perspective and a survivor-centred approach throughout its work;

- To engage with Sudanese parties and all other stakeholders, in particular United Nations agencies, civil society, refugees, the designated Expert on Human Rights in the Sudan, the field presence of the Office of the High Commissioner in Sudan, African Union bodies and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, in order to provide the support and expertise for the immediate improvement of the situation of human rights and the fight against impunity; and

- To ensure the complementarity and coordination of this effort with other efforts of the United Nations, the African Union and other appropriate regional and international entities, drawing on the expertise of, inter alia, the African Union and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights to the extent practicable;

- Decides to enhance the interactive dialogue on the situation of human rights in the Sudan, called for by the Human Rights Council in its resolution 50/1, at its 53rd session so as to include the participation of other stakeholders, in particular representatives of the African Union, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and civil society;

- Requests the independent investigative mechanism to present an oral briefing to the Human Rights Council at its 54th and 55th sessions, and a comprehensive written report at its 56th session, and to present its report to the General Assembly and other relevant international bodies; and

- Requests the Secretary-General to provide all the resources and expertise necessary to enable the Office of the High Commissioner to provide such administrative, technical and logistical support as is required to implement the provisions of the present resolution, in particular in the areas of fact-finding, legal analysis and evidence-collection, including regarding sexual and gender-based violence and specialized ballistic and forensic expertise.

- Requests the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to urgently organize on the most expeditious basis possible an independent investigative mechanism, comprising three existing international and regional human rights experts, for a period of one year, renewable as necessary, and complementing, consolidating and building upon the work of the designated Expert on Human Rights in the Sudan and the country office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, with the following mandate:

-

We thank you for your attention to these pressing issues and stand ready to provide your delegation with further information as required.

Sincerely,

First signatories (as of 26 April 2023):

- Act for Sudan

- Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture in the Central African Republic (ACAT-RCA)

- African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies (ACDHRS)

- African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS)

- AfricanDefenders (Pan-African Human Rights Defenders Network)

- Algerian Human Rights Network (Réseau Algérien des Droits de l’Homme)

- Amnesty International

- Angolan Human Rights Defenders Coalition

- Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

- Atrocities Watch Africa (AWA)

- Beam Reports – Sudan

- Belarusian Helsinki Committee

- Burkinabè Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CBDDH)

- Burundian Coalition of Human Rights Defenders (CBDDH)

- Cabo Verdean Network of Human Rights Defenders (RECADDH)

- Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

- Cameroon Women’s Peace Movement (CAWOPEM)

- Central African Network of Human Rights Defenders (REDHAC)

- Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) – Mozambique

- Centre de Formation et de Documentation sur les Droits de l’Homme (CDFDH) – Togo

- CIVICUS

- Coalition of Human Rights Defenders-Benin (CDDH-Bénin)

- Collectif Urgence Darfour

- CSW (Christian Solidarity Worldwide)

- DefendDefenders (East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project)

- EEPA – Europe External Programme with Africa

- Ethiopian Human Rights Defenders Center (EHRDC)

- FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights)

- Forum pour le Renforcement de la Société Civile (FORSC) – Burundi

- Gender Centre for Empowering Development (GenCED) – Ghana

- Gisa Group – Sudan

- Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect

- Horn of Africa Civil Society Forum (HoA Forum)

- Human Rights Defenders Coalition Malawi

- Human Rights Defenders Network – Sierra Leone

- Human Rights House Foundation

- Institut des Médias pour la Démocratie et les Droits de l’Homme (IM2DH) – Togo

- International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI)

- International Commission of Jurists

- International Refugee Rights Initiative (IRRI)

- International Service for Human Rights

- Ivorian Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CIDDH)

- Jews Against Genocide

- Journalists for Human Rights (JHR) – Sudan

- Justice Africa Sudan

- Justice Center for Advocacy and Legal Consultations – Sudan

- Libyan Human Rights Clinic (LHRC)

- Malian Coalition of Human Rights Defenders (COMADDH)

- MENA Rights Group

- Mozambique Human Rights Defenders Network (MozambiqueDefenders – RMDDH)

- NANHRI – Network of African National Human Rights Institutions

- National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders – Kenya

- National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders – Somalia

- National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders-Uganda (NCHRD-U)

- Network of Human Rights Journalists (NHRJ) – The Gambia

- Network of the Independent Commission for Human Rights in North Africa (CIDH Africa)

- Never Again Coalition

- Nigerien Human Rights Defenders Network (RNDDH)

- Pathways for Women’s Empowerment and Development (PaWED) – Cameroon

- PAX Netherlands

- PEN Belarus

- Physicians for Human Rights

- POS Foundation – Ghana

- Project Expedite Justice

- Protection International Africa

- REDRESS

- Regional Centre for Training and Development of Civil Society (RCDCS) – Sudan

- Réseau des Citoyens Probes (RCP) – Burundi

- Rights Georgia

- Rights for Peace

- Rights Realization Centre (RRC) – United Kingdom

- Salam for Democracy and Human Rights

- Society for Threatened Peoples

- Southern Africa Human Rights Defenders Network (Southern Defenders)

- South Sudan Human Rights Defenders Network (SSHRDN)

- Sudanese American Medical Association (SAMA)

- Sudanese American Public Affairs Association (SAPAA)

- Sudanese Women Rights Action

- Sudan Human Rights Hub

- Sudan NextGen Organization (SNG)

- Sudan Social Development Organisation

- Sudan Unlimited

- SUDO UK

- Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition (THRDC)

- The Institute for Social Accountability (TISA)

- Togolese Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CTDDH)

- Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH)

- Waging Peace

- World Council of Churches

- World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

- Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights

Annex: Key human rights issues in Sudan, pre-15 April 2023

Sudan’s human rights situation has been of utmost concern for decades. In successive letters to Permanent Missions to the UN Human Rights Council, Sudanese and international civil society groups highlighted outstanding human rights concerns dating back to the pre-2019 era, including near-complete impunity for grave human rights violations and abuses, some of which amounting to crimes under international law.

Civil society organisations also attempted to draw attention to post-2019 human rights issues, including the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters during and after the 2018-2019 popular protests and after the military coup of 25 October 2021. They repeatedly called for ongoing multilateral action, stressing that as the UN’s top human rights body, the Council had a responsibility to ensure scrutiny of Sudan’s human rights situation and to support the Sudanese people’s demands for freedom, justice, and peace.

During a special session held on 5 November 2021, the Council adopted a resolution requesting the High Commissioner to designate an Expert on Human Rights in the Sudan. As per resolution S-32/1, which was adopted by consensus, the Expert’s mandate will be ongoing “until the restoration of [Sudan’s] civilian-led Government.” As per Council resolution 50/1, also adopted by consensus, in July 2022, the Council requested the presentation of written reports and the holding of additional debates on Sudan’s human rights situation.

The violence that erupted on 15 April 2023, which resulted from persisting disagreements regarding security and military reforms and unaddressed issues of accountability of security forces and lack of security sector reform, came against a backdrop of severe restrictions on human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Observers’ and civil society actors’ fears of a deterioration of the situation, immediately prior to 15 April 2023, including in the form of an intensified crackdown on peaceful protesters in Khartoum and violence in the capital and in the conflict areas of Darfur, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan, as well as in Eastern Sudan, were well founded. These fears were made credible by the history of violence and abuse that characterises Sudan’s armed and security forces, including the SAF, the RSF, and the General Intelligence Service (GIS) (the new name of the infamous National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS)).

Since the 25 October 2021 coup, de facto authorities systematically used excessive and sometimes lethal force, as well as arbitrary detention to crack down on public assemblies. The situation was particularly dire for women and girls, who face discriminatory laws, policies, and practices, as well as sexual and gender-based violence, including rape and the threat of rape in relation to protests and conflict-related sexual violence in Sudan’s conflict areas.

National investigative bodies, such as the committee set up to investigate the 3 June 2019 massacre in Khartoum, had failed to publish any findings or identify any perpetrators.

The situation in Darfur, 20 years after armed conflict broke out between the Sudanese government and rebel groups, remained particularly concerning. Intercommunal and localised violence in Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile had escalated since October 2021, resulting in civilian casualties, destruction of property and human rights violations. Emergency laws and regulations remained in place, stifling the work of independent actors. In Blue Nile State, fighting had increased in scope and expanded to new areas.

Cruel, inhuman and degrading punishments that were common in the Al-Bashir regime were still being handed out by the courts of laws. Throughout the country, the Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) continued to unduly restrict the operations of civil society organisations, including through burdensome registration and re-registration requirements, restrictions to movement, and surveillance.

These added to long-standing, unaddressed human rights issues UN actors, experts, and independent human rights organisations identified during the three decades of the Al-Bashir regime. Among these issues, impunity for grave human rights violations and abuses remains near-complete.

As of early April 2023, the country was in a phase of political dialogue. On 5 December 2022, the Sudanese military and civilian representatives, including the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), which played a key role in the 2018-2019 revolution, signed a preliminary agreement, known as the Political Framework Agreement. The agreement was supposed to be a first step in paving the way for a comprehensive agreement on the transition, which was supposed to be led by civilians and lead to the holding of elections at the end of a two-year period. The agreement, however, excluded key issues such as justice and accountability. Strong disagreements persisted regarding key security and military reforms. Influential actors, including major political parties and the resistance committees, rejected the deal altogether.

The political stalemate and mounting tensions also threatened the implementation of the Juba Peace Agreement, signed on 3 October 2020 between the then Transitional Government and parties to the peace process, including armed groups that were involved in the conflicts that have affected several of Sudan’s regional States in the last three decades.

Related Content

11th Meeting of the Global Network of R2P Focal Points Outcome Document