Reflections on the UN General Assembly Debate on the Responsibility to Protect

The panel discussion convened by the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect and the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect reflected on the many achievements of the UN General Assembly (GA) debate, the perceptions about the debate and the way forward towards the implementation of the norm of responsibility to protect. The much anticipated debate on implementing the responsibility to protect was held on 23, 24 and 28 July. In one of the largest plenary debates of the General Assembly‗s 63rd session, 94 countries presented their positions on the responsibility to protect. Following the debate, on 14 September, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution A/63/L80 Rev. 1 entitled ―The Responsibility to Protect‖. The three paragraph resolution was co-sponsored by 67 member states and adopted by consensus. In it, the General Assembly recorded that it had received a report from the Secretary-General on the implementation of the 2005 World Summit Agreement, it had held a timely and productive debate on the report, it and intended to continue to engage on the issue of the responsibility to protect.

Dr. Monica Serrano asserted that the tone and substance of the debate indicated a clear consensus within the membership on the obligation to halt mass atrocities, with only four countries seeking to roll back the agreement made at the 2005 World Summit by heads of state. Countries from both North and South were overwhelmingly positive about the debate, and the very eloquent and forceful participation of the South dispelled the myth that R2P is a principle driven by the North. More than 50 countries endorsed the understanding of R2P as encompassing three pillars – the responsibility of the state to protect its populations; the responsibility of the international community to assist the state; and the responsibility of the international community to take timely and decisive action– and four crimes – genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

The issues on which member states expressed concerns included selectivity and the use of double standards in the implementation of the norm; the use of force and unilateral intervention; the restraint on the use of veto by the P5 in R2P situations; and respective roles of GA and the Security Council (SC) in implementing R2P. Only a few states endorsed the view expressed in the President of the General Assembly‘s (PGA) concept note that the UN needed to first solve the issue of poverty and development, before turning to security. The debate was forward looking and considered among others several concrete steps, ranging from ratification of human rights treaties to education and awareness raising around what R2P is, and to the strengthening of early warning and development of capacities at the national, regional and international level.

Ambassador Rosenthal explained that his personal, as well as his government‘s, support for R2P is an outgrowth of Guatemala‘s domestic conflict that ended in 1996. By elaborating on the experience of Guatemala, he acknowledged the basis of the inviolability of sovereignty and the norm of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of the state, but argued that linking sovereignty with responsibility was an important step. Every country has a responsibility to protect its population from the four crimes, and there should be consequences if it is unwilling to do so.

In the view of Ambassador Rosenthal, notwithstanding the personal views expressed by the PGA, and his convening of an informal interactive dialogue involving the participation of panelists known for their harsh criticism of R2P, 80 percent of the statements made by member states –as documented by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect—reflected positive attitudes both towards paragraphs 138 and 139, the Secretary General‘s report, and the need for the GA to continue its consideration of R2P.

A large number of countries did not see the need for a resolution, for even a procedural resolution, following up on the debate. For the skeptics, the conclusion by the PGA that ―the time for R2P had not yet come‖ sufficed. Among many member states that were supportive of R2P,in the light of the potential for a roll back of the commitment made in 2005, the view that no outcome was the best outcome prevailed. Yet, many member states did feel that a resolution was the best outcome; they shared four general beliefs:

-

-

- R2P is viable and should continue to be considered;

- Next steps on the matter should be defined by member states and not by the PGA;

- Any resolution should reflect consensus rather than a vote;

- Practically all nations accept the integrative nature of all three pillars.

-

Guatemala led the successful facilitation of the draft resolution based on these four beliefs. Sixty-seven member states representing every region in the world co-sponsored the resolution and it was passed and adopted by consensus. Ambassador Rosenthal pointed out that the resolution was important for two main reasons: First, it provided a basis for a future debate on R2P in the GA, which a summary by the PGA could not have done; and secondly, it expressed the view that a small but vociferous minority should not be able to impose its view on the membership.

As Thelma Ekiyor explained the debate was a success from the point of view of the civil society. In spite of low expectations, the debate provided an opportunity to hear a wide range of perspectives on R2P. This helped in establishing a distinction between those with legitimate concerns and the naysayers. For civil society and the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect, the aim was to dismiss the belief that R2P was a Western notion. R2P was discussed in Africa long before the World Summit and has been included in the institutional structure of ECOWAS.

The resolution is an important step forward. There is still a need to clarify R2P and to work on the grey areas, such as what the time frame for action is and who decides. The General Assembly debate was not supposed to reach consensus on all these questions, but it was the start of the conversation. In part, fears about R2P have a lot to do with the concerns about its misuse by powerful states, and the UN structure and not the norm itself. She concluded that now is the time to continue the discussions. The UN needs to look inwards and as civil society we need to ask how we can advance R2P in each region, as R2P will not have a one size fits all approach. She urged for partnerships between governments and civil society to be further enhanced to move R2P towards implementation.

Juan Mendez commented that while the 2005 Outcome Document had been approved by the SC and the GA, over the last years there has been a pushback on the norm and the debate was useful because it showed that there is an encouraging coalition of supporters from all over the world who endorsed the norm. Regional powers like India, South Africa, Brazil, Indonesia, and Japan which had been ambiguous about their position on R2P came to the debate and expressed their desire to work on the issue constructively. Many members of the Non-Aligned Movement also spoke in favor of R2P.

He distinguished R2P from humanitarian intervention and emphasized that R2P focuses on action at different points during the development of a crisis through pillars I and II. Also, as stated by many member states, all that R2P does is referenced in other existing norms including the Geneva conventions, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the use of force as per Chapter VII of the UN Charter

The norm of R2P is close to being crystallized. Apart from the question of its normative status, it can certainly be considered a doctrine. A doctrine does not need the consensus of all individual states to be operational, but it can help to organize and inform the work of the UN. The debate was thus necessary to begin a process within the UN Secretariat for the operationalization of R2P. The key immediate challenges include the need to decide the locus of decision-making in the Secretariat on R2P; to mainstream R2P so that all units of the Secretariat are willing to think in terms of R2P; to provide the Secretariat and the Security Council with resources to make this doctrine effective when the time comes; and to improve preparedness by developing an early warning capability with a focus on the prevention of mass atrocity crimes. He explained that development of early warning capabilities and early analysis will contribute to shaping political will, something which will always be a challenge.

During the Q &A, questions focused on the lack of political will with regards to R2P, the best strategies to move the norm forward and manage a small but very well organized group of member states that oppose R2P; how to ensure a wider acceptance of sovereign as responsibility; and on the crystallization of the norm.

On the question of political will, Mr. Mendez emphasized developing early warning capacities that look at situations from the perspective of mass atrocity prevention. Pressure should be applied on political actors before a situation deteriorates, focusing on what should be done and the consequences of inaction.

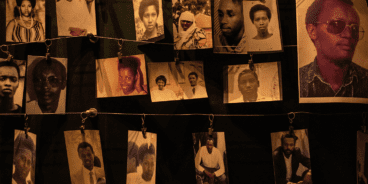

Ambassador Rosenthal noted that there has been gradual change in attitudes over the last few years. Any doctrine that contained the possibility of intervention would have been rejected 15 years ago, but now the boundaries of what is acceptable have changed. In order to bring more member states on board, the best strategy is to focus and work on the concerns that member states have, so that we can build a norm that will not tolerate another Rwanda.

As to the issue of sovereignty and responsibility, Dr. Serrano noted that in the debate, many member states accepted the construction of sovereignty as responsibility. The debate and the voices of the civil society demonstrated that there is an expectation of the UN system and the member states to fulfill their respective responsibilities. Ms. Ekiyor added that civil society has been the primary driver in the development of the norm of the responsibility to protect and that the UN as an institution has not promoted the norm. The hope now is that the resolution can push the UN to fulfill its commitment.

The discussion ended with Mr. Mendez noting that customary law is formed by opinio juris and developed by practice but R2P is in actuality a reference to existing norms. He argued that a norm does not have to be respected in all cases for it to be considered a norm. For example prohibition on torture is a norm, but it is not respected universally. The opinio juris with respect to R2P is that no one says that we can let thousands of people die or that we condone genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing.

Panelists:

-

-

- H.E. Mr. Gert Rosenthal, Permanent Representative of Guatemala to the United Nations

- Ms. Thelma Ekiyor, Executive Director, West Africa Civil Society Institute and Chair of the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect

- Dr. Mónica Serrano, Executive Director, Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect

-

Discussant:

-

-

- Mr. Juan Mendez, Former Special Adviser to the Secretary General for the Prevention of Genocide

-

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 389: Genocide Prevention and Awareness Month, Myanmar (Burma) and North Korea