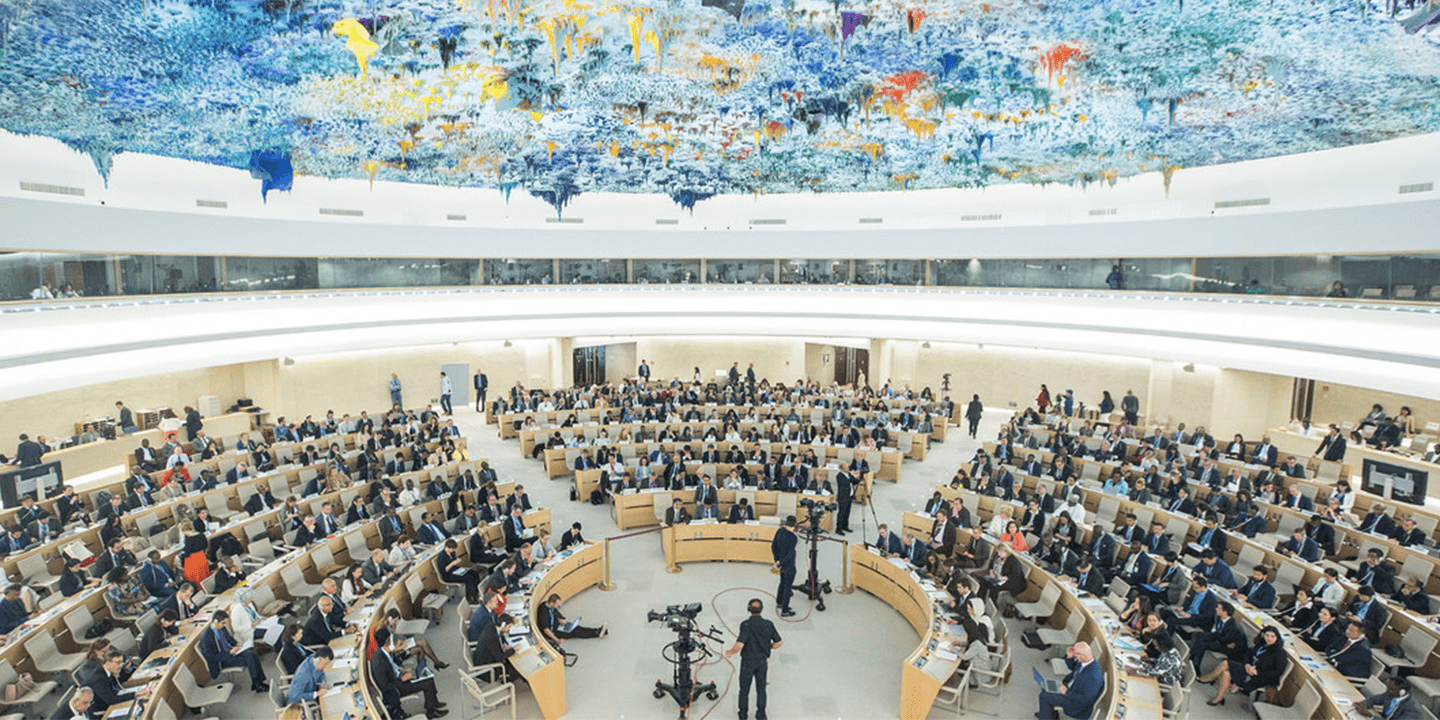

Recommendations for the 42nd Session of the Universal Periodic Review

Your Excellency,

In 2005 heads of state and government unanimously agreed on the responsibility of states to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Under the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), it is the primary responsibility of each individual state to protect their own population and the responsibility of the international community to assist them in doing so. The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) can play an important role in assessing each country’s institutional preparedness to protect human rights and prevent mass atrocities. During the 42nd session of the UPR working group, the Global Centre is respectfully encouraging member states to provide all states that are under review with the following recommendations, where applicable:

-

-

- Expeditiously appoint an R2P Focal Point – a senior government official responsible for the promotion of mass atrocity prevention at the national, regional and international level;

- Sign, ratify and implement the core instruments of International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), including the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Additional Protocols I and II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, Arms Trade Treaty, and 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict;

- In keeping with R2P’s Pillar II, request support from other states, as well as regional and international organizations, when risks exist that cannot be addressed by your state alone;

- Ensure that all national security forces respect human rights and IHL and fulfill their responsibility to protect all populations within the territory of your state, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or any other status;

- Support accountability for atrocity crimes and all relevant institutions of international justice;

- Issue open invitations to HRC-mandated Special Procedures and fully cooperate with all other HRC mechanisms and procedures;

- Protect human rights defenders and the media, as well as the rights of civil society to operate freely, safely and independently.

-

In addition to these general recommendations, the Global Centre respectfully asks you to consider the tailored recommendations provided below for Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Pakistan

In 2014 government security forces launched a crackdown on armed extremist groups in Pakistan, primarily Tehrik-i-Taliban (TPP) and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, as well as affiliates that have historically been active in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Despite sustained military operations by the government, there has been a resurgence in armed extremist activity in Pakistan in recent years, primarily from the TPP and the so-called Islamic State. On 28 November the TPP announced the resumption of country-wide attacks. Armed extremist groups primarily target religious minorities and law enforcement officials. The number of people killed in attacks by such groups has increased annually since 2020, with the death of at least 440 civilians and security forces in 2021 and 536 in 2022, according to the South Asia Terrorism Portal.

In addition, Pakistan’s draconian blasphemy laws — which call for the execution of those found guilty of insulting Islam — continue to be used to justify persecution of the country’s ethnoreligious minority groups, as well as activists, journalists and critics of the government. Pakistan’s law enforcement agencies are responsible for numerous human rights abuses, including arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. Additionally, Pakistan’s penal code criminalizes same-sex sexual conduct, leaving LGBTQ+ individuals at risk of police abuse, other violence and systematic and institutionalized discrimination. Violence against women and girls, including rape, murder, domestic violence and forced marriage, persists.

Since former Prime Minister Imran Khan was ousted as the country’s leader in a vote of no confidence in April, the country has experienced significant political and economic instability. Pakistan’s government appears to be unable or unwilling to adequately address short-term and long-term atrocity risks in a context of wider human rights violations and abuses. The Global Centre therefore urges you to include the following recommendations to Pakistan during the UPR session on 30 January:

-

-

- Conduct credible and transparent investigations and, where applicable, prosecute security forces and other state agents responsible for atrocity crimes, and publicly report on the status of investigations;

- In 2023 establish a national action plan to investigate the enforced disappearances of human rights defenders, journalists and members of minority groups, as well as share the findings with the families of the disappeared;

- Request technical assistance and support from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in ensuring that counterterrorism policies and operations meet international human rights standards;

- Develop a human rights-focused anti-terrorism strategy to address atrocity risks posed by extremist groups, including through community engagement to respond to insecurity and other drivers of violence;

- Immediately abolish violence, persecution, threats and intimidation against minority groups, civil society activists and LGBTQ+ individuals.

-

The Global Centre further respectfully encourages you to consider the following advanced question for the review of Pakistan:

-

-

- What steps is the government of Pakistan taking to address the ongoing atrocity threat that terrorist groups like the TPP pose to ethnic minorities and other vulnerable populations?

-

Sri Lanka

From 1983 to 2009 the Sri Lankan government and the insurgent Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam engaged in a brutal civil war that was characterized by mass atrocities, including war crimes, committed by both sides of the conflict. In 2015, through HRC Resolution 30/1, the Sri Lankan government committed to establish a Commission for truth, justice, reconciliation and non-recurrence, as well as a judicial mechanism to investigate alleged violations of IHL and IHRL. However, OHCHR has reported as recently as October 2022 that successive governments in Sri Lanka have consistently failed to pursue an effective transitional justice process to hold perpetrators accountable for gross human rights violations, including mass atrocities. In 2020 Sri Lanka withdrew its support for HRC Resolution 40/1 – and related resolutions 30/1 and 34/1 – all of which pertain to reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka.

In a report published 4 October 2022 the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that without comprehensive reform serious human rights violations and atrocities risk being repeated as the state apparatus, and some of its members credibly implicated in alleged grave crimes and human rights violations, remain in positions of power. Although the war ended over a decade ago, the military continues to maintain a significant presence in north and east Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka is also experiencing a concerning trend toward ethno-religious majoritarianism, which has been characterized by divisive and exclusivist rhetoric. Additionally, the ongoing militarization of the civilian government threatens human rights protection and risks undermining democratic institutions. The intelligence services, military and police are continuing to surveil, intimidate and harass journalists, human rights defenders, families of the disappeared and people involved in memorialization initiatives, particularly in the north and east. The military’s response to peaceful protests has often been characterized by excessive force.

OHCHR has warned that the current devastating economic crisis in Sri Lanka further undermines human rights protection. As the Sri Lankan government appears to lack the capacity and will to establish a transitional justice process and address the root causes of past and ongoing systematic violations and abuses, the Global Centre urges you to include the following recommendations to Sri Lanka during the UPR session on 1 February:

-

-

- Fully implement the recommendations provided by OHCHR in its latest report, A/HRC/51/5, including reforming the security sector and preparing a comprehensive strategy on transitional justice and accountability that addresses outstanding commitments to establish a truth commission and a judicial mechanism to prosecute perpetrators of past atrocity crimes;

- Conduct credible and transparent investigations into alleged perpetrators of atrocity crimes, regardless of rank, affiliation or current position within the government or security forces, and provide regular public reports on government efforts to advance investigations;

- Formally invite OHCHR to strengthen its country presence and monitor the situation on the ground, provide technical assistance to authorities and work with civil society organizations documenting ongoing violations and abuses;

- Respect the fundamental right to peaceful assembly and refrain from using excessive and deadly force against protesters;

- Commit to cooperate with OHCHR, as well as all other HRC-mandated mechanisms and procedures, and issue open invitations to Special Procedures mandate holders requesting to visit the country.

-

The Global Centre further respectfully encourages you to consider the following advanced questions for the review of Sri Lanka:

-

-

- What has hindered the process of establishing a truth commission and a judicial mechanism? What steps has the Sri Lankan government taken to address these challenges and complete the process of establishing them?

- How is the Sri Lankan government working to limit the impact of political and economic instability on human rights and the country’s persecuted populations?

-

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 427: Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Afghanistan