R2P: A Norm of the Past or Future?

On 28 February 2014 Global Centre for R2P Executive Director Dr. Simon Adams published the following article on OpenCanada.org.

The Danish physicist Niels Bohr, an avowed anti-Nazi who also won the Nobel Prize for his work on quantum mechanics, once quipped that “prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” The question of whether the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) is a norm of the past or future depends, fundamentally, upon your disposition. Those dismayed by NATO’s “mission creep” while protecting civilians in Libya, or alternatively, by the bitter failure of the UN Security Council to stem the bloodletting in Syria, may well answer that R2P’s moment has passed.

On the other hand, R2P – which was first formulated in the report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty in 2001 and adopted at the UN World Summit in 2005 – has been described by the former UN Special Adviser on the Responsibility to Protect Dr. Edward Luck as the fastest developing international norm in history. At a meeting we both attended at the British Houses of Parliament under the aegis of the all-parliamentary group for mass atrocity prevention, Dr. Luck compared the trajectory of R2P since 2005 to the evolution of human rights norms after the Second World War.

Despite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the human rights situation in much of the world was still wretched during the 1950s as Cold War hypocrisies plagued the international system. Human rights terminology was worn thin by opportunistic misuse. It is only from the vantage point of a new century that we can look back and proclaim that despite this, human rights still made gradual, but cumulative, normative progress over the second half of the twentieth century. The underlying ideas were not fatally weakened by inconsistent application. The enduring challenge was to work towards universal application.

Less than a decade after R2P appeared in paragraphs 138 and 139 of the World Summit Outcome Document, it is difficult to get a precise measurement of its normative success. But what we can determine is if the tide is rising or ebbing.

Acceptance of R2P is steadily increasing. Following the UN World Summit, the Responsibility to Protect was reaffirmed in Security Council Resolution 1674 (2006) and Resolution 1894 (2009) – both dealing with the protection of civilians during armed conflict. The Council also made reference to R2P in Resolution 1706 (2006) on Darfur. Although there have been divisive debates about R2P with regard to Sri Lanka and elsewhere, Libya and Syria have provided R2P with its biggest challenges. These cases are difficult precisely because they raise issues of accountability and coercion to halt mass atrocities – matters the UN Security Council has always struggled to address with undeviating and proximate determination.

Yet, despite rancour over Syria, the Security Council still invoked R2P more often in the year after Libya and the start of Syria crisis than it had done in the five years prior.

In addition to R2P resolutions on Libya (Resolutions 1970 and 1973), between March 2011 and March 2012 the Security Council invoked R2P in resolutions on Côte d’ Ivoire (Resolution 1975), South Sudan (Resolution 1996), and Yemen (Resolution 2014). There were also two follow-up resolutions on Libya (Resolutions 2016 and 2040). Resolution 2085 of 19 December 2012, which authorized an intervention force in Mali, mandated the force to “support the Malian authorities in their primary responsibility to protect the population.”

During 2011 and 2012, R2P was also invoked in four UN Security Council Presidential Statements. These statements, which require consensus to be adopted, focused on combating the Lords Resistance Army in Central Africa and the maintenance of international security. In 2013, two Presidential Statements have included R2P elements. The first, adopted on 12 February, explicitly reaffirmed a commitment to R2P and said that the Council “recognizes that States bear the primary responsibility to protect civilians.” Similarly, a 15 April statement, adopted during Rwanda’s presidency, not only stressed “the importance of the responsibility to protect as outlined in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document,” but also that the “Council further underlines the role of the international community in encouraging and helping States, including through capacity building, to meet their primary responsibility.”

While Presidential Statements, unlike Security Council resolutions, are not binding under international law, they are significant when it comes to building normative acceptance. Importantly, these statements were adopted with the consent of China, Russia and Pakistan – three states who have at times been critical of R2P as an alleged western tool for “regime change”.

The reality is that R2P has moved from moral abstraction to being part of an ongoing debate about the practicalities of implementing measures to protect civilians who might otherwise be marked for death. It is for this reason that at the end of 2011 UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon argued that, “I would far prefer the growing pains of an idea whose time has come to sterile debates about principles that are never put into practice.”

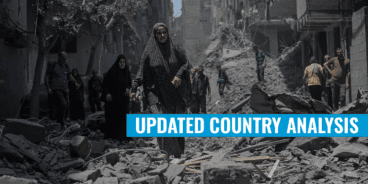

Perhaps a better question to ask is whether the circumstances that gave rise to the adoption of the Responsibility to Protect at the 2005 UN World Summit have ceased to exist. Are mass atrocity crimes a thing of the past? The answer from the perspective of those burying their dead in Syria, Sudan or the Democratic Republic of the Congo would be clear enough. Indeed, when the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect published its first edition of the “R2P Monitor” in January 2012, there were nine countries where mass atrocities were either already occurring, or were at serious risk of being committed. Ten editions and eighteen months later, there are still nine countries in the R2P Monitor. But, crucially, they are not the same nine. While some situations have resisted resolution (Syria, Sudan and DR Congo) and others have clearly worsened (Burma/Myanmar, South Sudan and Nigeria), concerted domestic and international collaboration decreased the risk in other countries.

To cite just one example, on 4 March, 2013 Kenyans voted in the country’s first general elections since violence following the December 2007 presidential ballot left 1,133 people dead and more than 663,000 displaced. Concerted diplomatic action led by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan not only ended atrocities and led to a power-sharing government, it was also lauded as the first example of “R2P in practice.”

International engagement since then, coupled with widespread constitutional and political reforms enacted by the Kenyan government, helped ensure Kenya did not suffer a bloody post-electoral redux in 2013.

R2P is concerned with the prevention of mass atrocity crimes, not the outcome of elections. In Kenya, however, R2P offered an analytical lens to understand the nature of threat facing the country, while also providing a tool for mobilizing preventive action. Kenya also reminds us that while both governments and civil society talk endlessly about the importance of prevention, it is the part of R2P that we understand the least. Partly to address this deficit, in 2010 the governments of Denmark and Ghana embarked upon the R2P Focal Points initiative. Since then the governments of Australia and Costa Rica have also joined the facilitating group.

A R2P Focal Point is a senior government official responsible for the promotion of mass atrocity prevention at the national level and who also participates in a Global Network of R2P Focal Points. The third annual meeting of the Global Network was held during June 2013 in Accra, Ghana. More than thirty-five countries and three regional organizations attended. The meeting was notable for the extent to which appointed R2P Focal Points were able to share direct experience regarding the practicalities of mass atrocity prevention. Pragmatic lessons from peacekeeping operations, or regarding security sector reform and peacebuilding were discussed at length, including by representatives of states still emerging from conflict. Altogether, since September 2010 thirty countries, representing both the global north and south, have appointed a national R2P Focal Point. These states are actively building a “community of commitment” that increases our international capacity to prevent mass atrocities. Such a network would have been politically inconceivable only a few years ago.

Leo Tolstoy, the legendary Russian writer, once condemned government as “an association of men who do violence to the rest of us.” Fundamental to R2P is the notion that sovereignty entails responsibility and is not simply a license to kill. But the Responsibility to Protect, like the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is still only as strong as the determination of the international community to uphold its principles. We cannot let future normative progress be a prisoner of the past.

Related Content

Populations at Risk