Overcoming atrocities: An opportunity for change in Burundi

Earlier this month, on 18 June, Burundi swore in Évariste Ndayishimiye as the country’s new president, nearly one month after winning a contested election against Agathon Rwasa and other opposition candidates. The accelerated inauguration process followed the unexpected death of President Pierre Nkurunziza on 8 June. Amidst this rapid transition – initially set to take place in August – Burundians and the international community are waiting to see if the new government will seize upon this unique moment in the country’s history. Can President Ndayishimiye and the new government reverse the policies pursued by President Nkurunziza that deepened societal divisions and resulted in years of political conflict?

Nkurunziza’s election in 2005 – following a bloody civil war during which atrocities were committed and an estimated 350,000 people were killed – brought Burundians hope for a better future. But ten years later, Nkurunziza buried this hope when he stood for a controversial third term in 2015. This was perceived by many as a violation of the Arusha Peace Agreement that helped to end the civil war. Since then, Burundi has been trapped in a downward spiral of state-led persecution, fear and repression and many predicted the situation in the country could potentially return to atrocities and renewed violence.

Six months prior to the May 2020 election, the Human Rights Council (HRC)-mandated Commission of Inquiry (CoI) on Burundi warned that the elections may trigger renewed crimes against humanity. When news broke early on 20 May that authorities had blocked social networks – including Whatsapp, Facebook and Twitter – many observers expected the worst. But the elections passed without a violent showdown between government and opposition supporters – in particular those belonging to ruling CNDD-FDD (Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie–Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie) party and the main opposition party, Rwasa’s Congrès National pour la Liberté.

President Ndayishimiye and the CNDD-FDD now have a chance to restore trust in state institutions, and re-engage with the region and the wider international community. As the country looks to Ndayishimiye for leadership, the new government must commit to ending human rights violations and abuses, ensuring full accountability for all victims of mass atrocity crimes, and addressing the root causes of such crimes to prevent their recurrence.

Nkurunziza and beyond: addressing atrocity risks

In their September 2019 report, the CoI concluded that, “the eight common risk factors identified in the [UN] Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes are clearly present in Burundi, and there is a significant number of indicators for each of them.” Despite the relatively peaceful election, many of these risk factors remain present in the country today. Notably, the CoI highlighted the weakness of state structures, continued governmental support for groups accused of involvement in human rights violations and abuses – particularly the Imbonerakure, the ruling party’s youth wing – and severe restrictions on civil society and independent media.

Burundi has a long legacy of atrocities, including those committed during its 1993-2005 civil war, which was largely fought between ethnic Hutu armed groups and the Tutsi-dominated army. However, many of the risk factors present today are linked to the 2015 political crisis sparked by Nkurunziza’s third term. Since then the government and its supporters, particularly the Imbonerakure, have perpetuated a climate of fear as they systematically attempted to silence dissent.

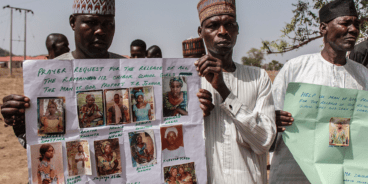

For nearly five years, alleged and actual opponents of the ruling party have been persecuted, killed, tortured or disappeared. To hide their actions, the ruling party also embarked on a crackdown on civil society and independent media, effectively making it a life-threatening endeavor for journalists and human rights activists to report on the ongoing violence. These patterns intensified ahead of key political events – including the 2020 elections, and a controversial referendum two years earlier. A deep mistrust in state institutions has also kept more than 330,000 Burundians who fled violence in 2015 from returning to their homeland.

Pervasive impunity has meant that most perpetrators do not fear investigation, let alone prosecution. Although the government established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate atrocity crimes perpetrated prior to 2008, it has been accused of complicity in the government’s attempt to “rewrite the history of Burundi,” including through selective investigations and the politicization of past atrocities. Far from fostering reconciliation, inflammatory rhetoric, hate speech and incitement to violence by senior government officials – including the late President himself – aggravated divisions in recent years.

During Nkurunziza’s last term, the Burundian government also systematically isolated itself from the region and the wider international community. After Burundi’s withdrawal from the ICC took effect in 2017, it also forced the UN Human Rights office in the country to close its doors. Members of the CoI – declared personae non gratae by Burundian authorities – were never allowed to enter the country. Instead, Burundian officials publicly threatened the Commissioners, warning they would “bring them to justice” for reporting on the country’s human rights crisis. Most recently, a week before the elections, the government expelled members of the World Health Organization and threatened anyone within the country who dared to criticize their weak response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unless President Ndayishimiye addresses the risk factors identified by the CoI, little will change in Burundi. The new government should recommit to upholding its responsibility to protect by ending persecution and repression, strengthening state institutions and tackling pervasive impunity. This will require tough political decisions, including the demobilization and disarming of the Imbonerakure and implementing measures to ensure that security forces adhere to the highest human rights standards.

Above all, the incoming government must prioritize independent, credible and transparent investigations into all human rights abuses and violations ordered and committed since 2015, identify those responsible, and put in place a victim-centered approach to justice and accountability. This would send a strong signal to all perpetrators that they will be held accountable for their crimes, and to victims, that justice will be served.

Broad reforms, including establishing genuine and unbiased truth and reconciliation process, supporting an independent judicial system, and allowing for a vibrant civil society, are indispensable for the regeneration of Burundi. The international community and regional organizations, like the East African Community, should help reinvigorate Burundi’s engagement with international mechanisms and wherever possible support the government in implementing reforms to prevent further atrocities and protect human rights.

An opportunity for change in Burundi

Fifteen years ago, as the country emerged from a devastating armed conflict and a period of unspeakable atrocities, Burundians had hope for a future without violence. But as persecution, violence and fear became a defining feature of daily life in Burundi over the past five years, this optimism drained away. With the sudden and unexpected death of Pierre Nkurunziza and a new President in office, the incoming government has another historic opportunity. During his inauguration ceremony on 18 June, President Ndayishimiye pledged to “ensure the national unity and cohesion of the Burundian people.” The next few months will show whether he is ready to live up to this promise and transcend the legacy of atrocities and bitter divisions bequeathed to him by his predecessor.

Related Content

Elections, Power Transitions and the Risk of Atrocity Crimes