Mass Atrocity Crimes are Everybody’s, Not Nobody’s, Business

The following is a contribution by Gareth Evans at the First Dialogue Advisory Group (DAG)-3 Quarks Daily (3QD) Peace and Justice Symposium alongside David Petrasek and Kenneth Roth. Original essay available here.

David Petrasek is not alone in his anxiety that the new ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P) doctrine will be misused to the point of doing more harm than good. His arguments are well articulated and need to be taken seriously by R2P advocates. But in seeking to answer them, what I will be defending is the R2P norm that has originated and evolved over the last decade, not the miscellany of different positions that he lumps together as the ‘new interventionism’.

Petrasek’s ‘new interventionists’ seem to embrace not only R2P supporters who understand and accept that coercive military intervention is defensible only in the most extreme, exceptional and clearly defined circumstances, but also latter-day enthusiasts for the kind of ‘humanitarian intervention’ or ‘right to intervene’ doctrine re-popularised, after a century’s lapse, by Bernard Kouchner in the 1990s, and more recently embraced by commentators like Anne-Marie Slaughter, who is a fine scholar but has rarely seen an argument she didn’t like for shedding blood in a good cause.

The difference between the ‘humanitarian intervention’ and the new R2P norm unanimously adopted by the UN General Assembly at the 2005 World Summit really is crucial. It’s not just a matter of acknowledging, as Petrasek does, that R2P is about much more than just the use of force, focusing as it does on preventive strategies, both long and short term, plus a whole suite of non-military reaction options (including diplomatic persuasion, targeted sanctions and threat of international criminal prosecution) should prevention fail.

The more important point is that R2P approaches coercive military force itself with a completely different mindset, one much less enthusiastic about military solutions. And it does so both because R2P advocates are both acutely conscious of the demonstrable risks associated with too cavalier an approach to military instruments, and determined to achieve and maintain an international consensus – sadly lacking in the past – that mass atrocity crimes are everybody’s, not nobody’s, business.

For most humanitarian intervention enthusiasts, civilian protection situations potentially justifying intervention are quite broadly defined; ‘sending in the marines’ is seen as more or less the only response option; the only relevant criterion for the use of coercive military force is whether it will halt the immediate harm in question; and the only relevant players are those capable of exercising it.

For R2P advocates, on the other hand, the focus is on a quite narrow class of civilian protection cases – not those involving human rights violations or conflict at large, but only where genocide, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity or large-scale war crimes are in issue. And even in these cases, coercive military force is not the only resort but an absolute last resort, to be considered only when no lesser option could possibly work, and when other prudential criteria are satisfied. Moreover, to sustain a rule-based international order, it should only be applied – other than in self-defence – with the approval of the UN Security Council.

The issue of prudential criteria for the use of force is central to the argument about the use and misuse of R2P. Although no formal guidelines have so far been agreed by the Security Council or General Assembly – that remains unfinished business – five criteria have clearly emerged from the debate over the last decade, are crucial to the coherence of the doctrine, and command widespread acceptance among R2P advocates. They are as follows:

First, seriousness of risk: is the threatened harm of such a kind and scale as to justify prima facie the use of force? Second, is the primary purpose of the proposed military action is to halt or avert the threat in question, whatever other secondary motives might be in play? Third, last resort: has every non-military option been fully explored and the judgment reasonably made that nothing less than military force could halt or avert the harm in question? Fourth, proportionality: are the scale, duration, and intensity of the proposed military action the minimum necessary to meet the threat? Fifth, and usually the toughest legitimacy test, balance of consequences: will those at risk ultimately be better or worse off, and the scale of suffering greater or less?

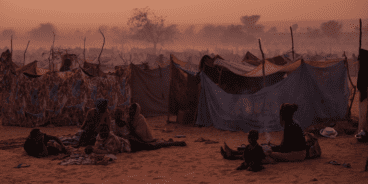

It should be obvious that these criteria, properly applied, set a very high bar for military intervention. Maybe too high for those appalled by the lack of international inaction in cases which seem to morally cry out for it, but it is the over-reach (and perceived erratic application), of interventionist doctrine, not its possible under-reach, that Petrasek is most concerned about. Many of the cases of ‘selectivity’ he complains of are simply those where either the threshold requirement of actual or imminent mass atrocity crimes (as distinct from lesser human rights violations, or a general conflict situation) has not been satisfied, or one or more of these prudential tests have not been met. In particular the ‘balance of consequences’ test will often rule out coercive intervention even if all the other guidelines are satisfied: I would argue that such was the case, for example, in Darfur in the mid-2000s and is the case in Syria now (though the arguments for and against indirect intervention, by supplying arms to the Free Syrian Army, are more finely balanced).

The reality is that it is only very rarely that the stars will align in such a way that not only are all the prudential criteria generally seen to be satisfied but the Security Council actually agrees on the use of coercive force. That happened in February-March 2011, with both Cote d’Ivoire and Libya, with the Council explicitly invoking R2P. But since then, the controversy over the alleged over-reach by the NATO-led coalition in implementing the Libyan mandate has produced paralysis in the Council when it has come to applying any leverage at all, including through wholly non-military measures, on Syria.

It is too harsh to describe the Libyan intervention, as Petrasek seems to want to, as a cynical misuse of R2P doctrine. The P3 – the U.S., UK and France – have some credibility when they argue that if civilians were to be protected house-to-house in areas like Tripoli under Gaddafi’s direct control, that could only be by overturning his whole regime, and that if one side was taken in a civil war, it was because one-sided regime killing sometimes leads to civilians acquiring arms to fight back and recruiting army defectors, and that this should not change the moral equation.

But the weakness of the P3 position is that as the intervention proceeded other Council members were given sufficient information to enable these arguments to be evaluated, and no real opportunity to debate them. Maybe not all the BRICS states (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) are to be believed when they say, as they do, that had better process been followed, more common ground could have been achieved. But they can be when they say they feel bruised by the P3’s dismissiveness during the Libyan campaign – and that those bruises will have to heal before any consensus can be expected on tough responses to such situations in the future.

The better news is that a way forward has opened up. Brazil has been arguing for some months that the R2P concept, as it has evolved so far, needs not overthrowing but rather supplementing by a complementary set of principles and procedures which it has labeled ‘responsibility while protecting’ (‘RWP’). Its two key proposals are for a set of criteria – essentially of the kind listed above – to be fully debated and taken into account before the Security Council mandates any use of military force, and for some kind of enhanced monitoring and review processes which would enable such mandates to be seriously debated by all Council members during their implementation phase. The P3’s initially dismissive response has shown signs of softening as the realization deepens that unless some moves in this direction are made, it will be difficult ever again to secure un-vetoed majority support in the Council for tough action (even falling considerably short of military action) in a hard mass atrocity crime case.

Humanitarian intervention doctrine, in its 1990s form and as continuing to be advocated by some, particularly in the U.S., is for all practical purposes dead internationally, but the much more nuanced R2P is very much alive, even if the doctrine is still evolving, and its completely effective practical implementation is going to be work in progress for some time yet.

The most difficult area in which to achieve and sustain genuine international consensus will always be at the sharp end of the R2P response spectrum. Renewing the kind of consensus that was evident in March 2011 will come too late to be very helpful in solving the present crisis in Syria, and maybe other hard cases. But there are very few policymakers anywhere in the world who would relish a return to the bad old days of Rwanda, Srbrenica and Kosovo: either total, disastrous inaction in the face of mass atrocity crimes where a strong military response carried no obvious downside risks, or action being taken without Security Council authorization.

Working to iron out the remaining wrinkles in R2P doctrine, and create a really sustainable international consensus about how to employ it to end mass atrocity crimes once and for all, would be a more constructive use of David Petrasek’s abundant talent and experience than adding, to an already considerable academic pile, one more layer of rather over-hyped angst about the risks of interventionist over-reach.

Related Content

Twenty years of the Responsibility to Protect and the unfulfilled promise in Darfur