Joint NGO Letter on the rule of law in China

Across the People’s Republic of China, human rights violations are a systemic reality. Over the past year, the UN has once again documented legal and policy frameworks that fail to protect against discrimination; stigmatise Islam and stifle freedom of religious belief; undermine a wide range of socioeconomic rights and those who defend them; and permit gross violations of due process, including secret trials and arbitrary and incommunicado detention.

Over the past year, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet and other international human rights experts, as well as governments have pressed for access to China, in particular to Uyghur, Tibetan and other ethnic areas. The High Commissioner has urged dialogue and a de-escalation of violence in Hong Kong, following allegations of excessive use of force by police to disperse massive public protests and the criminalisation of demonstrators.

Independent experts of the UN Human Rights Council have requested information and prompt action from the government regarding a broad range of alleged violations and especially the criminalisation of human rights defenders and civil society, such as citizen journalists, lawyers, democracy movement leaders, religious leaders, workers’ rights activists, social workers, public health advocates and students.

In June of this year, more than two dozen governments informed the High Commissioner and the Human Rights Council president of their concerns about the use of re-education camps to target Uyghur and other Muslim minority groups in western China. They reiterated the need for prompt, independent and unfettered access.

Despite these efforts at engagement, the Chinese government has refused to allow independent visits of relevant human rights experts, including the Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council; refused constructive dialogue, sowed disinformation and stoked violence in Hong Kong; used a push for sinicisation to eliminate cultural and religious diversity; and continued a fierce campaign against critics within China and many abroad, including other States. Chinese officials have stated, clearly and forcefully in public and in private, that ‘China is a country of rule of law’ and ‘will not accept interference in its internal affairs’.

This is patently misleading.

The Communist Party of China uses China’s laws to maintain state power, not to ensure justice. Overly broad charges that do not comply with the principle of legality are used to wrongfully detain, prosecute, and convict individuals for the peaceful exercise of internationally protected rights and participation in public affairs. In effect, any person who expresses views that differ from the Party narrative, or who seeks to highlight negative impacts of Party and government policies, can be caught in the crosshairs of criminalisation.

The Chinese government has refined and replicated a practice of characterizing all difference or dissent as terrorism, subversion, or a threat to national security. The tactics deployed in Hong Kong are regularly used against Uyghur and Tibetan peoples to justify a hard-line crackdown on the legitimate exercise of human rights. This is a dangerous departure from international human rights standards.

Furthermore, the Chinese government’s human rights record is no longer an issue limited by its borders. The government has actively used laws and practices to disappear and detain foreign nationals, restrict access to information overseas, conduct surveillance of Chinese nationals and other exile communities, embolden its law enforcement outside Chinese borders, and impede public participation, sustainable development and transparency in third countries where China has political and economic interests.

Human rights defenders of all kinds have been specifically targeted. The silence of the international community has not only allowed this to decimate civil society within China, but also to endanger civil society, defenders and other individuals critical of the Chinese government wherever they may be, including in the halls of the UN.

The same laws that allow the arbitrary deprivation of liberty of lawyers, public interest advocates, housing rights activists, and Christians in China’s wealthy eastern areas are further refined and weaponised against ethnic and religious minorities in the west of the country, including Tibet, where international access is a significant concern. The large-scale detention program in Xinjiang, which has detained Uyghurs and other minorities, may amount to crimes against humanity.

The worrying departures from the rule of law that led many companies and business associations to express concerns about the draft Extradition Bills in Hong Kong earlier this year have also allowed incommunicado detention and the torture and other ill-treatment of detainees. These violations, coupled with no access to effective remedies, have contributed to a growing number of deaths in custody, such as the 13 July 2017 death of Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo.

Well-intentioned requests for information and calls for reform from United Nations officials and government leaders are important because they demonstrate to human rights defenders and their families that their struggles are visible. However, such calls for justice have fallen on deaf ears.

A system with no checks or balances, which lacks an independent judiciary, and which interprets and applies laws as merely tools to ensure regime control and stability cannot uphold any human rights standards, much less the ‘highest standards’ to which the Chinese government has committed as a Council member.

We call on the international community, and specifically the UN Human Rights Council, to stand in solidarity with the victims of human rights violations by the Chinese government, wherever they may be. This includes using all available avenues to press the Chinese government to comply with its obligations to ensure human rights and provide access to effective remedies for violations, as outlined in the UN Charter and human rights treaties.

We urge any government or intergovernmental organisation engaged in technical assistance and cooperation with the People’s Republic of China to suspend rule of law cooperation until China takes concrete and measurable steps to implement recommendations received from the UN human rights mechanisms, as assessed by those bodies and independent experts.

The defence of human rights is not a criminal act.

The peaceful expression of dissent is not extremism.

Universal rights are not subject to arbitrary limits under the guise of countering terrorism.

In particular, we urge the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to actively raise, publicly and privately, all pressing human rights issues in the People’s Republic of China. To remain silent on those most marginalised or vulnerable, including ethnic groups such as Uyghurs, Tibetans and Mongols, risks their further stigmatisation.

We also encourage the High Commissioner to commit publicly to taking concrete steps to ensure that the Office’s mandate – ‘to promote and protect all human rights for all people’ – can be realized in regard to the People’s Republic of China and those whose rights it violates. This work has never been more important, nor more imperilled.

Thank you for your support.

Related Publications

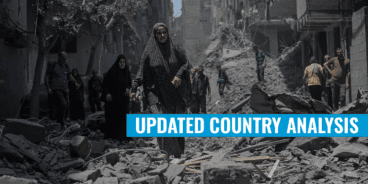

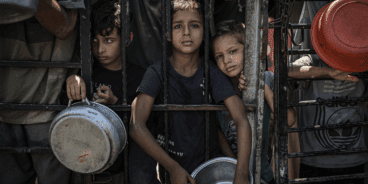

Atrocity Alert No. 448: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Sudan and China