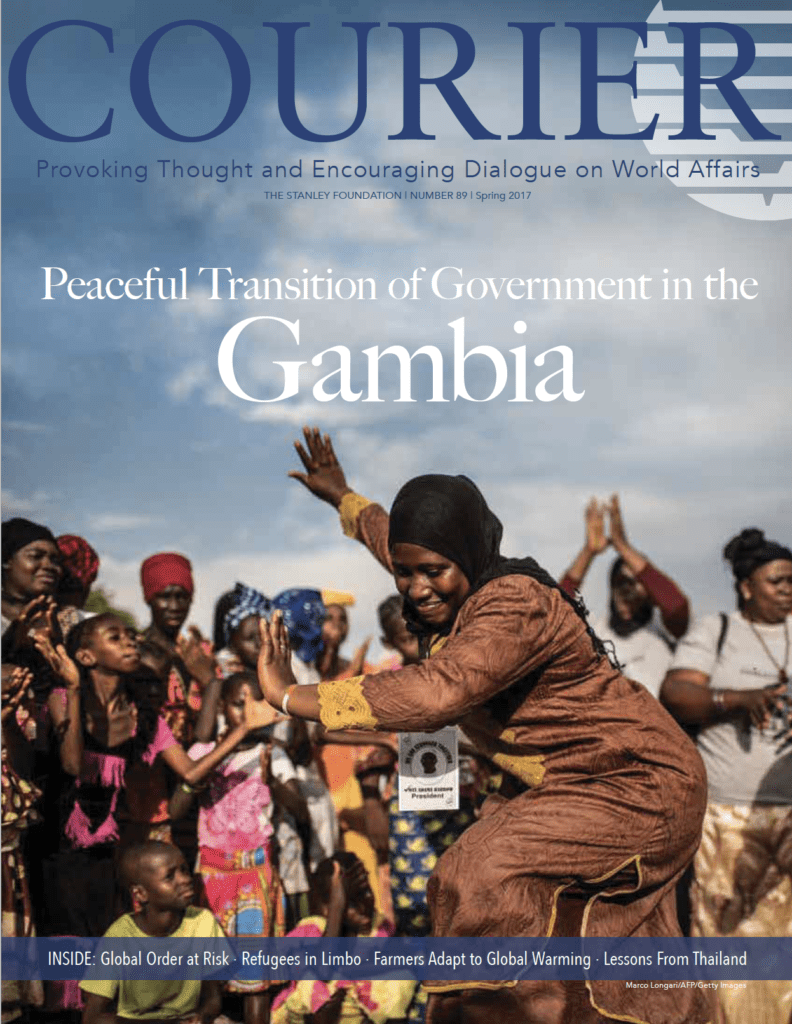

Conflict Averted Without Anyone Firing a Shot: Subregional, Multilateral Action Helps Prevent Atrocities in The Gambia

The Gambia, the smallest country in mainland Africa, made big news in January 2017, when Adama Barrow became the nation’s third president after defeating incumbant Yahya Jammeh in the December 2016 elections. Jammeh initially refused to accept the results, which triggered a constitutional crisis and threat of mass conflict.

Following is the story of how mass violence was averted was averted through multilateral regional intervention and peaceful transition of governance.

Despite initially conceding defeat to Barrow in the Gambia’s presidential election on December 1, 2016, Jammeh refused to step down, and his party, the Alliance for Patriot Reorientation and Construction, filed petitions to challenge the election results. What should have been the Gambia’s first peaceful transition of power since its independence in 1965 instead became a political crisis that put populations at risk of mass atrocity crimes.

Despite initially conceding defeat to Barrow in the Gambia’s presidential election on December 1, 2016, Jammeh refused to step down, and his party, the Alliance for Patriot Reorientation and Construction, filed petitions to challenge the election results. What should have been the Gambia’s first peaceful transition of power since its independence in 1965 instead became a political crisis that put populations at risk of mass atrocity crimes.

Ultimately, Jammeh’s refusal to accept the election results and cede power after more than 22 years in office did not result in widespread violence or civilian casualties. However, throughout the six-week period between the election and his eventual resignation, political tensions pushed the country to the brink of disaster. According to the United Nations, at least 45,000 people fled The Gambia amid the political crisis.

Due in large part to concerted efforts at preventive diplomacy by regional actors—including the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union, and the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS) – a potential armed conflict and widespread civil unrest were averted. On January 19, 2017, Barrow was inaugurated in Senegal. Jammeh went into exile in Equatorial Guinea two days later.

Elections are one risk factor for atrocity crimes, sometimes as a result of political parties deliberately manipulating identity-based differences between populations or because of fears of a winner-take-all environment, in which electoral defeat represents political and economic marginalization for large groups of people. In the case of the Gambia, however, neither theand imminent threat to populations. Rather, Jammeh’s disturbing and inflammatory rhetoric, his long history of human rights violations, his apparent willingness to use force to protect his power, and the threat of an ECOWAS military intervention combined to create a delicate and dangerous situation.

History of Escalated Violence

Jammeh had a long history of inciting divisions based on ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation. In June 2016, he threatened to exterminate the entire Mandinka ethnic group, whom he did not consider authentic Gambians. He routinely endangered lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, notoriously threatening to “slit the throats” of all gay men in the Gambia. In the weeks following his electoral defeat, some of his supporters blamed political instability in the country on gays and their alleged foreign supporters, signaling growing fractures in Gambian society that Jammeh could use to mobilize his political supporters.

As president, Jammeh consistently demonstrated he had both the will and capacity to systematically persecute civil- ians he perceived to be a threat to his power. Under his leadership, Gambian authorities participated in forced disappearances, arbitrary detention, torture, and other human rights violations against journalists, human rights defenders, and political opponents. In the initial weeks following his electoral defeat, Jammeh retained the loyalty of senior commanders within the military and tried to forcibly shut down independent radio and media sources.

As the end of his mandate neared, Jammeh made several public declarations threatening to use force to protect his interests. This included a speech in December in which he declared any protests by opposition supporters would be met with extreme force and several threats that if ECOWAS intervened in support of Barrow, it would constitute a “declaration of war.” On January 17, 2017, Jammeh declared a state of emergency, banning any acts of “disobedience” that could threaten his presidency, curtailing civil liberties, and placing additional restrictions on independent media. The state of emergency was not revoked until January 24, 2017, after President Barrow returned to the country.

Regional Cooperation and Intervention

The crisis in the Gambia was neutralized by timely and consistent action on the part of ECOWAS member states and UNOWAS. On December 13, 2016, Jammeh’s security forces blocked access to the electoral commission, and ECOWAS sent a delegation of presidents from four West African countries to the Gambia. After the delegation failed to persuade Jammeh to concede to Barrow, it swiftly formed a formal mediation team and prepared standby forces for a potential military intervention.

Throughout January 2017, ECOWAS leaders and UNOWAS responded with consistent diplomatic and military pres- sure, including clear demands and deadlines for Jammeh to commit to a democratic transition or risk being forcibly removed from the country. On January 18, 2017, the last day of Jammeh’s presidential mandate, a regional intervention appeared imminent. Senegalese troops were on the border with the Gambia, and Nigerian warships deployed off the coast. Although troops did cross into the Gambia, the ECOWAS intervention was halted after Jammeh accepted an amnesty offer and resigned, leaving the country.

In a briefing to the UN Security Council on January 25, 2017, the head of UNOWAS called the outcome “a success of preventive diplomacy that has been achieved through the mobilization of regional actors in perfect coordination with the international community.”

Timely Action Before Atrocities Occurred

ECOWAS has indeed been a leading example of how sub- regional organizations, in collaboration with the United Nations and other regional groups, can uphold the international norm of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), a political commitment by states to take measures to protect populations from war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and ethnic cleansing, and, when necessary, to take timely action when states are manifestly failing to prevent such crimes from occurring. The situation in the Gambia merited ECOWAS’s attention from the day Jammeh contested the results, rather than waiting for atrocities to occur.

Together with the head of UNOWAS, ECOWAS leaders put consistent pressure on Jammeh, making clear the organiza- tion was prepared to adopt forceful measures—including the credible threat of a military intervention—should the president refuse to step down or escalate repressive violence against the population. Senegal played a pivotal role in linking the actions of the United Nations and ECOWAS, acting not just as a neighbor of the Gambia and member of ECOWAS but using its elected seat on the Security Council to ensure the United Nations remained engaged with the situation.

While many of the proximate threats to populations in the Gambia were alleviated with the peaceful departure of Jammeh, the risk to populations has not completely subsided. Barrow has undertaken various measures to reassure populations of the Gambia’s respect for human rights, international institutions, and normative mecha-of his predecessor, announcing the Gambia would rejoin the Commonwealth and would not leave the International Criminal Court. Barrow has also released hundreds of prisoners arbitrarily detained by the previous government. The new government has requested that ECOWAS maintain a small force within the country for six months, until the political situation has fully stabilized. Other potential sources of risk have also been alleviated as military officials have pledged their allegiance to the new government.

Nevertheless, societal cleavages that Jammeh deliberately deepened in order to retain power still need to be addressed through national reconciliation efforts to ensure that conflict does not arise between perceived Jammeh supporters and those who support Barrow. Additional concerns remain regarding the amnesty Jammeh was granted for crimes perpetrated under his leadership and allegations that he embezzled millions of dollars before fleeing. It also remains important to hold security forces and other govern-and potential crimes under international law to truly reconcile and move forward in the Gambia.

Read Next

UN Human Rights Council Elections for 2025-2027 and the Responsibility to Protect

Expert Voices on Atrocity Prevention Episode 31: Christopher Fomunyoh