Atrocity Alert No. 248: Myanmar (Burma), Ethiopia and Syria

Atrocity Alert is a weekly publication by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect highlighting situations where populations are at risk of, or are enduring, mass atrocity crimes.

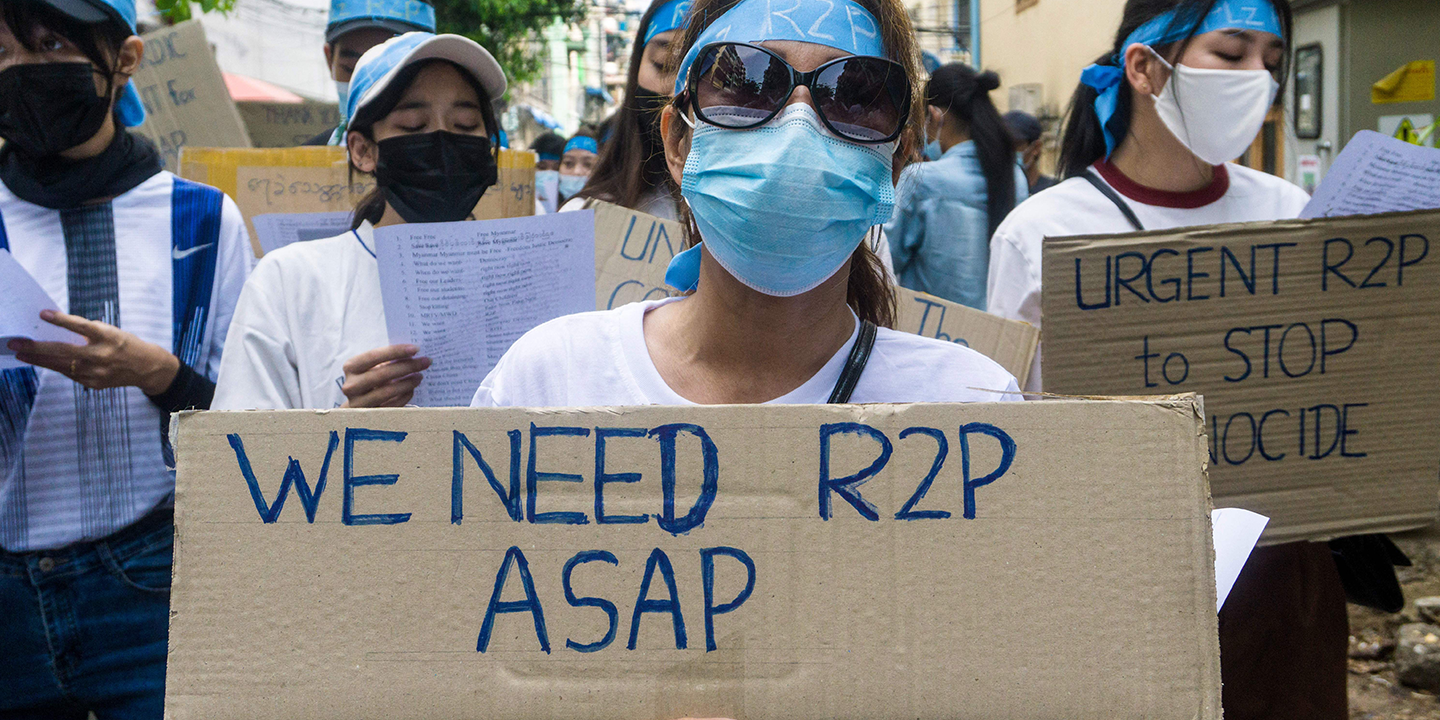

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights warns Myanmar could become the next Syria

On Friday, 9 April, at least 82 civilians were killed by Myanmar’s security forces in the city of Bago, about 90 kilometers (56 miles) northeast of Yangon. During their assault on anti-coup protesters in the city, the security forces used assault rifles, heavy machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, hand grenades and mortar fire. There were also reports that medical personnel were prevented from tending to the wounded.

That same day Myanmar state television reported that 23 people, including captured protesters, had been sentenced to death following closed trials in a military court. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, at least 715 people have been killed by the security forces since 1 February and more than 3,070 are currently detained for resisting the military coup.

On 13 April the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, issued a chilling warning regarding the deteriorating situation in Myanmar, cautioning that “there are clear echoes of Syria in 2011. There too, we saw peaceful protests met with unnecessary and clearly disproportionate force… I fear the situation in Myanmar is heading towards a full-blown conflict. States must not allow the deadly mistakes of the past in Syria and elsewhere to be repeated.” Bachelet noted that “the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights at the time [Navi Pillay] warned in 2011 that the failure of the international community to respond with united resolve could be disastrous for Syria and beyond. The past ten years have shown just how horrific the consequences have been for millions of civilians.”

As the massacre was unfolding in Bago, the UN Security Council (UNSC) held an informal “Arria formula” meeting on Myanmar. One of the briefers, Daw Zin Mar Aung, from the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, as well as Myanmar’s Ambassador to the UN, Kyaw Moe Tun, called on the Council to uphold its responsibility to protect and take decisive action in response to the violence in Myanmar. The UNSC has issued three statements since the military seized power on 1 February, but is yet to impose any measures in response to atrocities perpetrated by the junta.

The UN Special Envoy on Myanmar, Christine Schraner Burgener, arrived in Thailand on 9 April for a regional visit. Special Envoy Burgener requested face-to-face meetings with Myanmar’s military officials but was refused entry to the country.

Nadira Kourt, Program Manager at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, said, “the time for the UN Security Council, ASEAN and other states to move from statements to action is long overdue. Myanmar needs a global arms embargo, internationally binding sanctions on senior military officials and businesses, and the situation should be referred to the International Criminal Court. Excuses and inaction in the face of these ongoing atrocities is unconscionable and inexcusable.”

Hundreds killed in surge of inter-communal violence across Ethiopia

Ethnic violence and inter-communal conflict have sharply increased in Ethiopia, with more than 600 people killed in the Benishangul-Gumuz, Oromia and Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s regions since September last year. Endale Haile, Ethiopia’s chief ombudsman, has publicly claimed that 300 people were also killed in the Amhara region over several days during March when Oromo and Amhara communities clashed in North Shewa and the Oromo Special Zone.

Most of the victims of the March violence in the Amhara region were killed by gunfire, but some were attacked with machetes, sticks and stones. Ombudsman Endale reported that over 1,500 homes were also burned and destroyed. The violence reportedly began after an ethnic Oromo imam was killed outside a mosque in the Oromo Special Zone on 19 March. Ombudsman Endale lamented that the government’s response to this violence had been too slow and stated that “the government is responsible to protect and secure civilians.”

At least 100 civilians were also killed in the areas of Haruk and Gewane between Ethiopia’s Afar and Somali regions over 2-6 April. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed stated that special forces from Ethiopia’s eastern Somali region attacked the areas, which are formally part of Afar. During the violence, Somali regional forces and militias reportedly indiscriminately fired on Afar pastoralists and killed children and women. Ethnic tensions and recurring conflict between forces from the Afar and Somali regions partly originates from a 2014 redrawing of regional borders that resulted in the transfer of three towns to Afar.

According to the Ethiopian government, an estimated 1.7 million people also remain displaced in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, where there have been widespread reports of war crimes and ethnic cleansing since armed hostilities broke out between the regional authorities and the federal government last November. Ethiopia is due to hold general elections on 5 June, but given the rise of ethnic conflict, regional disputes and an ongoing humanitarian crisis, there are growing fears for the safety and security of voters.

OPCW confirms Syrian Air Force dropped chemical weapons on civilians

On 12 April 2021 the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) Investigation and Identification Team (IIT) released its second report on the use of chemical weapons in Syria. The report attributes responsibility to government forces for the use of chlorine gas on the night of 4 February 2018 in the city of Saraqib. According to the IIT, a military helicopter under the control of the “Tiger Forces” of the Syrian Arab Air Force dropped at least one cylinder containing chlorine on eastern Saraqib. The IIT confirmed that twelve individuals suffered symptoms of chemical poisoning as a consequence of the attack.

The use of chemical weapons, including chlorine gas, is illegal under international law and constitutes a war crime. A spokesperson for UN Secretary General António Guterres said that he had received the IIT report and that the “Secretary-General strongly condemns the use of chemical weapons and reiterates his position that the use of chemical weapons anywhere, by anyone, and under any circumstances, is intolerable, and impunity for their use is equally unacceptable.”

The OPCW has documented the illegal use of chemical weapons in Syria for over seven years. In 2014 the OPCW created a Fact-Finding Mission, which confirmed that chlorine and mustard gas had been used against civilian populations. These findings supported the work of the UN Security Council-mandated OPCW-Joint Investigative Mechanism (OPCW-JIM), which determined that the Syrian government used chemical weapons on numerous occasions. In October and November 2017 Russia vetoed three Security Council resolutions aimed at renewing the mandate of the OPCW-JIM.

The IIT focuses on incidents for which the OPCW-JIM did not reach a final conclusion and is mandated to identify specific perpetrators. The IIT’s first report, released on 8 April 2020, found that the Syrian Arab Air Force used chemical weapons – including chlorine and sarin – in three separate incidents in March 2017 in the town of Ltamenah.

The prohibition of chemical weapons is one of the oldest and universally respected norms of the international community, codified by the Geneva Protocol of 1925 and the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention, of which Syria became a signatory in 2013. The international community must hold those who have used chemical weapons in Syria accountable under international law, regardless of their position or affiliation.

Related Content