Atrocity Alert No. 213: Sudan, Central African Republic and Hate Speech

Atrocity Alert is a weekly publication by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect highlighting situations where populations are at risk of, or are enduring, mass atrocity crimes.

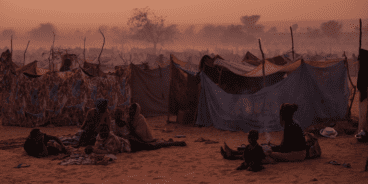

Growing inter-communal violence plagues Darfur

Violence and insecurity are increasing throughout the Darfur region of Sudan, where dozens of people have been killed and several villages destroyed in recent weeks. This includes violence on Saturday, 25 July, when approximately 500 armed men attacked Masteri village, killing at least 60 people from the ethnic Masalit community. In a separate incident that same day, another armed group attacked the Um Doss area in South Darfur, killing at least 20 people.

The precarious security situation in Darfur has been a major challenge for Sudan’s new government. Violence has been intensifying in Darfur since January when clashes between Arab and Masalit communities near El Geneina resulted in at least 70 people being killed and 40,000 displaced. Since the beginning of July, people throughout Darfur have protested against the growing insecurity, calling on the government to protect vulnerable civilians. The government declared a state of emergency after an armed group attacked a protest camp on 13 July, killing 13 people.

Darfur has a long history of violence between nomadic herdsmen (many of whom identify as Arabs) and farmers (who identify as African) over access to water, land and other essential resources. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, recent violence has jeopardized the agricultural season and is exacerbating Darfur’s ongoing humanitarian crisis. Nearly 2.8 million people are estimated to be severely food insecure across Darfur.

The former military dictatorship in Sudan was responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in Darfur. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed and key figures in the government, including President Omar al-Bashir, were indicted by the International Criminal Court.

Despite increasing armed conflict in Darfur, the UN Security Council (UNSC) is currently discussing an “exit strategy” for the African Union-UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID). The UNSC is expected to decide on a possible drawdown process before the end of December.

Juliette Paauwe, Senior Research Analyst at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, said that, “the protection of civilians must remain central to any proposed UN mission to replace UNAMID. The UNSC should continue to support Sudan’s democratic transition and assist the transitional authorities as they attempt to stabilize the security situation, uphold human rights and resolve ongoing inter-communal conflicts.”

Tensions build ahead of December elections in Central African Republic

Amidst rising tensions and insecurity in the Central African Republic (CAR), on 25 July deposed former President François Bozizé announced his candidacy for the upcoming presidential elections, scheduled for 27 December. Bozizé is currently under UN sanctions for undermining the peace, stability and security of CAR, and is subject to an arrest warrant issued by the government for alleged crimes against humanity and incitement to commit genocide.Bozizé took power following a military coup during 2003, serving as president until he was overthrown in a 2013 armed rebellion by the mainly Muslim Séléka rebel alliance. Although Bozizé lived in exile until December 2019, his overthrow plunged the country into a civil war, with widespread atrocities perpetrated by various armed groups. More than 1.2 million Central Africans have fled the country since 2013 and 2.6 million are still in need of humanitarian assistance.

Political tensions in CAR have risen since April, when deputies from the National Assembly introduced a bill that would have allowed current president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra, to remain in power should the COVID-19 pandemic cause the postponement of elections. On 5 June the Constitutional Court ruled that the proposed amendment was unconstitutional. An opposition coalition has also accused the government of fraud during the voter registration process.

Although fighting in CAR has decreased since February 2019 following the signing of a historic peace agreement between the government and various armed groups, attacks against civilians continue. Signatory armed groups routinely violate the terms of the agreement and some have exploited the peace deal to consolidate their control over territory.

Christine Caldera, Research Analyst at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, stated, “the upcoming elections are an opportunity to continue CAR’s shift away from its past history of atrocities and conflict, and towards the stability that Central Africans so desperately desire. The African Union, which is a guarantor of CAR’s peace agreement, should ensure that no candidate or political party is able to use the election to incite further violence and foment instability.”

COVID-19 contributes to hate speech pandemic

Since the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the spread of the virus has led to a rise of misinformation, stigmatization, discrimination and hate speech. UN Secretary-General António Guterres has stated that, “the pandemic continues to unleash a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering.”

In various countries across the globe individuals have been targeted on the basis of their group identity. In the United States, which has the largest COVID-19 death toll in the world, individuals perceived as ethnically Chinese have been vilified and falsely accused of spreading the virus, resulting in physical assaults. Similar dynamics exist in other countries, but with the focus on other marginalized minorities, including Roma in parts of Europe, internally displaced persons in the Central African Republic, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community in Iraq and Israel.

A recently released report by the Asia Centre focuses on how hate speech has proliferated throughout Southeast Asia due to COVID-19. In Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand migrant workers have experienced increased stigmatization and some have been socially ostracized as potential “threats” to health and security.

According to the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, hate speech is often amplified through social media. During April, messages targeting the ethnic Rohingya community proliferated on social media in Malaysia. Many posts included dehumanizing language and images, accused Rohingya of posing a threat to community health, and called for refugees to be forcibly returned to Myanmar. That same month, Malaysian authorities also denied entry to hundreds of Rohingya asylum seekers who were stranded in boats off their coast.

Hate speech can serve as an important indicator of potential human rights violations and abuses, and can provide early warning regarding the developing threat of mass atrocity crimes. In Myanmar, the proliferation of hate speech, when combined with discriminatory laws and policies, helped create an environment that led to the military’s so-called “clearance operations” during 2017, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths and the forced displacement of over 700,000 Rohingya. Those atrocities, and the hate speech that preceded them, has led to Myanmar being accused of genocide at the International Court of Justice.

In these times of an unprecedented global pandemic, it is essential that all states actively counter hate speech, including through legislation that outlaws the vilification of people on the basis of their ethnic, religious or group identity. Such regulations should be targeted in a way that minimizes their potential misuse to silence legitimate dissent or stifle genuine public debate. All UN member states should also adopt and implement the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Related Content

Twenty years of the Responsibility to Protect and the unfulfilled promise in Darfur