Atrocity Alert No. 150: Myanmar (Burma), Sudan, Burkina Faso and Rwanda

Atrocity Alert is a weekly publication by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect highlighting situations where populations are at risk of, or are enduring, mass atrocity crimes.

Myanmar’s military deploys helicopters against civilians

On 3 April military helicopters flew over southern Buthidaung township in Rakhine State, bombing the area and reportedly killing approximately 30 Rohingya civilians. At the time of the attack the victims were gathering bamboo and tending their fields. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) condemned the incident, stating that it may constitute a war crime.

The bombing occurred amidst intensifying clashes between Myanmar’s military (Tatmadaw) and the Arakan Army – an armed group seeking greater autonomy for the ethnic Rakhine Buddhist population. According to the UN, fighting between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army has already displaced more than 26,000 civilians. OHCHR has called upon the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army to immediately cease hostilities and restore humanitarian access to all areas of northern Rakhine State.

Recent developments underscore the complex history of ethnicity and conflict in Rakhine State. Rakhine is home to the ethnic Rohingya population, more than 720,000 of whom fled so-called “clearance operations” launched by Myanmar’s security forces in August 2017. Some ethnic Rakhine civilians collaborated with the security forces in atrocities that led to the Rohingya exodus.

Despite the international Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar documenting that the Tatmadaw’s 2017 operations against the Rohingya possibly constituted genocide under international law, the government has consistently denied that atrocities took place and has failed to hold perpetrators accountable. This has allowed senior officers and military units that were responsible for atrocities to participate in recent operations. While condemning the 3 April attack, the OHCHR spokesperson, Ravina Shamdasani, noted that, “the Myanmar military is again carrying out attacks against its own civilians” and that the “consequences of impunity will continue to be deadly.”

The government must ensure that all military operations against the Arakan Army are conducted in strict adherence with international law and do not target civilians. The international community should continue to impose targeted sanctions and pursue accountability for all those with command responsibility for genocide and other mass atrocity crimes committed in Rakhine State.

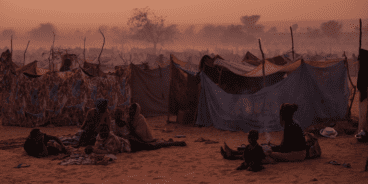

Civilians at risk as protests continue and the army fractures in Sudan

At a mass rally that started last Saturday, 6 April, in Khartoum, tens of thousands of protesters demanded an end to political corruption and called for the resignation of President Omar Al-Bashir, who has held power since a 1989 military coup. More than 20 people have been killed and 2,495 arrested since Saturday.

For the first time since demonstrations began on 19 December, protesters in Khartoum reached the headquarters of Sudan’s military, a complex that also houses the Ministry of Defense as well as President Bashir’s residence. On Monday, 8 April, troops from the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) and paramilitary units that include former Janjaweed fighters responsible for atrocities in Darfur, attempted to disperse the protesters using live ammunition and tear gas. Soldiers from the Sudanese Armed Forces intervened and protected the protesters, representing a potential fracturing of Sudan’s security apparatus. Five soldiers have reportedly been killed since Saturday in clashes with the NISS.

In order to secure his position, on 22 February President Bashir declared a state of emergency, banned demonstrations, dissolved central and state governments, and appointed military officers to government positions. President Bashir’s emergency measures and potential infighting within the security services leaves civilians at increasing risk if the situation continues to escalate. President Bashir has a long history of using extreme violence to secure his rule and is currently under indictment by the International Criminal Court for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide committed in Darfur.

In a statement on 9 April the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, asserted that Sudan’s authorities have an “over-arching responsibility” to protect the protesters. At the time of publication, tens of thousands of people were still staging a sit-in outside military headquarters in Khartoum. A spokesman for the police said that they had “ordered all forces” not to “intervene against the citizens or peaceful rallies.” As the crisis continues, the police and Sudanese Armed Forces should defend the universal right to freedom of assembly, association and expression and protect all unarmed civilians against any attempted use of disproportionate and deadly force.

Inter-communal violence and atrocities in Burkina Faso

More than 60 civilians were killed in a series of inter-communal clashes in northern Burkina Faso on 31 March and 1 April. The attacks started near Arbinda, Soum Province, following the killing of a religious leader and six of his family members by unidentified armed men. The killings sparked reprisal attacks the following day.

Populations in Burkina Faso have been at growing risk as both inter-communal violence and attacks by armed extremist groups have intensified across the Sahel region over the past year. During March Human Rights Watch reported on atrocities perpetrated by both armed extremist groups and the security forces in Soum Province since mid-2018. The Burkinabe security forces have allegedly detained and summarily executed members of the ethnic Peuhl community based upon their perceived affiliation with Ansaroul Islam and other armed extremist groups. Meanwhile, armed groups have attacked civilians and exploited inter-communal tensions as a means of expanding their influence.

According to Reuters, 499 people were killed between November 2018 and March this year during attacks on civilians in Burkina Faso. The UN Office on the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs says that more than 70,000 people have fled their homes during the first two months of 2019 alone and that ongoing violence has resulted in the closure of more than 1,100 schools.

One week before the Arbinda attack the UN Security Council met with leaders in Ouagadoudou as part of a visit to the Sahel region. The government of Burkina Faso, with support of the regional G5 Sahel Force, should bolster security in Soum Province and implement programs to mediate inter-communal tensions and control arms proliferation. While combatting Ansaroul Islam and other armed groups, it is essential that the government ensures that its efforts to counter violent extremism do not further exacerbate inter-communal tensions and are undertaken in strict compliance with international law.

Rwanda marks 25 years since the genocide against the Tutsi

Last Sunday, 7 April, marked the 25th anniversary of the start of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. The official three-month remembrance period marks the time between April and July of 1994 when approximately one million Rwandans were murdered. These tragic events later served as the impetus for all UN member states to unanimously commit themselves at the World Summit in 2005 to the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

Despite progress in the 25 years since 1994, the international community still struggles to consistently uphold this commitment. Mass atrocity crimes continue to be perpetrated against vulnerable populations in various parts of the world, including genocide committed against the Yazidi population in Iraq and against the Rohingya minority in Myanmar. The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect released a statement on the 25th anniversary, contributed to various media stories on the significance of the UN’s failure in Rwanda, and participated in memorial events in New York and elsewhere.

Read Next

Related Publications

Atrocity Alert No. 436: Haiti, Myanmar (Burma) and Syria

Twenty years of the Responsibility to Protect and the unfulfilled promise in Darfur