At a critical juncture for Burundi, the Special Rapporteur’s mandate remains vital

To Permanent Representatives of Member and Observer States of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (Geneva, Switzerland)

Excellencies,

As serious human rights violations continue to be committed in Burundi in a context of widespread impunity, and as the country prepares for legislative and presidential elections in a tense national and regional environment, the UN Human Rights Council should maintain its scrutiny.

At its upcoming 57th session (9 September-11 October 2024), the Council should extend the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Burundi. It should make clear that any future change of approach by the Council will be tied to structural reforms and tangible improvements in the country’s human rights record, rather than political developments.

~ ~ ~

Nine years after the outbreak of the still unresolved 2015 crisis, which followed the announcement by former President Pierre Nkurunziza that he would run for a third term in office (which the East African Court of Justice later ruled unconstitutional), Burundi’s human rights situation remains of serious concern. Changes since President Évariste Ndayishimiye was sworn in, in June 2020, did not bring about structural reforms to address long-standing human rights, governance, justice, and rule of law concerns. Many of the issues highlighted in reports by the UN Independent Investigation on Burundi (UNIIB), the Commission of Inquiry (CoI), the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the Special Rapporteur on Burundi, and independent civil society organisations, remain. Human rights violations and abuses continue with impunity.

These violations include extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and detentions, acts of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, sexual and gender-based violence, undue restrictions to the rights to freedom of opinion, expression, peaceful assembly and association, and serious violations of economic, social and cultural rights.

Suspected perpetrators include state and para-state actors, namely government officials, members of law enforcement and security forces, including the police and National Intelligence Service (SNR), and members of the ruling CNDD-FDD party’s youth league, known as the Imbonerakure. No senior officials have been held accountable for violations in relation to the repression of 2015 protests and its aftermath or for the targeting of political opposition members and supporters, human rights defenders (HRDs), journalists, and other critical and independent voices.

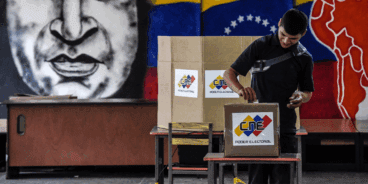

Legislative elections are planned for May 2025, eight months after the Human Rights Council’s 57th session, when the Council will consider a written report by the Special Rapporteur. Following a reform that instituted a seven-year term, presidential elections are planned for May 2027. As the country has entered the first of these two successive election periods, and in light of previous cycles of violence prior to, during, and after elections, we stress the following issues, which require the international community’s utmost attention.

First, risk factors of further violations. Several of the Risk Factors outlined in the UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes are present in Burundi. They include, at the very least, numerous Indicators that fall under Risk Factors 1 to 8. These Risk Factors and their associated Indicators, which the CoI introduced and relied on for its reporting on Burundi ahead of the 2020 elections, are based on the principles of prevention and early warning. They include, among others: (i) the existence of a security crisis, armed conflict in neighboring countries, political instability and tensions, and acute poverty; (ii) a record of serious violations of international law, impunity, and widespread mistrust in state institutions; (iii) the weakness of state structures, including the lack of an independent judiciary and high levels of corruption; (iv) drivers of violence, including ideologies based on extremist versions of identity; (v) a strong culture of obedience to authority; (vi) a closed civic space and lack of international media attention; (vii) the government’s refusal to allow the presence of NGOs and other international actors, and inflammatory rhetoric and hate speech; and (viii) triggering factors or events that may seriously exacerbate existing conditions, such as elections and pivotal activities related to elections.

The past few months have been marked by an increase in hate speech and inflammatory rhetoric, including at the highest political level, as well as by a further increase in the pressure authorities exert over civic space. In addition to previously reported patterns of attacks against HRDs, journalists and civil society organisations, in recent months, prominent media outlet Iwacu has been subjected to severe threats. While a presidential decree dated 14 August 2024 granted Floriane Irangabiye a pardon, which resulted in her release two days later, another journalist, Sandra Muhoza, remains arbitrarily detained. They should never have been detained in the first place. Despite her acquittal on charges of “slanderous denunciation,” at the time of writing, trade-unionist Émilienne Sibomana remained in detention. The authorities’ refusal to release her is likely related to the politically sensitive nature of her case – and emblematic of the widespread impunity high-ranking officials enjoy in Burundi.

The Burundian human rights crisis is also compounded by a volatile security situation, both inside the country and in the sub-region. Armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and cross-border violence risk increasing instability and tensions along ethnic lines in the Great Lakes region and in Burundi.

With Burundi at this critical juncture, Agathon Rwasa, the leader of the main opposition party, the National Congress for Freedom (CNL), was controversially ousted while on a trip outside the country, a move the Pan-African Opposition Leaders Network condemned as an “unlawful takeover” orchestrated by the Burundian Government. Many CNL members and supporters have reportedly left the country since, due to safety concerns.

Second, Burundi’s economic situation has worsened and grave violations of economic, social and cultural rights are increasingly at the forefront of the country’s human rights crisis.

Burundi remains among the world’s poorest countries in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. Most Burundians live in poverty and face the negative consequences of inflation, as well as fuel shortages, shortages in commodities and electricity, and lack of access to health services. The cessation of activities of state-owned companies illustrates the aggravating economic situation. Natural disasters, including floods, and a sanitation crisis, compound socio-economic and humanitarian challenges.

In northern Burundi, local authorities have since early 2024 launched a massive campaign against “concubinage” (the cohabitation of a married person with someone who is not their spouse), which is illegal under Burundian law and which they claim is a “sin” that prevents the country from developing. This hunt for “concubines” has resulted in at least (as at the end of May 2024) 900 women and 3,600 children being driven out of their homes in Ngozi Province alone. These unlawful evictions are discriminatory, leaving women homeless and thousands of children out of school. In other parts of the country, it has been reported that people claiming compensation for land expropriations by the Government have faced threats by the SNR.

The Burundian Government has failed to tackle the country’s economic crisis and to address financial mismanagement, chronic shortages of fuel, and spiraling prices. These failures, alongside the war in Ukraine and climate-related shocks, have exacerbated food insecurity in Burundi. President Ndayishimiye publicly dismissed widespread concerns over inflation and food insecurity. His comments have sparked outcry and indignation.

~ ~ ~

The Government of Burundi continues to disregard or minimise the severity of human rights challenges in the country. It refuses to grant access to and meaningfully cooperate with independent human rights bodies and mechanisms, and has effectively ceased its cooperation with the Council’s mechanisms, including in 2016 by declaring members of the UNIIB personæ non gratæ, by rejecting all visit requests by the CoI and other Council-appointed independent experts, and by refusing to cooperate with the Special Rapporteur. In 2019, the OHCHR had to close its country office at the Government’s request.

Immediately after his appointment, in April 2022, the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Fortuné Gaetan Zongo, expressed his willingness to explore avenues for cooperation with the Government of Burundi. All his attempts to engage, including visit requests, have either been rejected or remained unanswered.

In this context, the National Independent Human Rights Commission’s (CNIDH) lack of independence means that there is no nationally-mandated mechanism that is able or willing to protect human rights, including by investigating and reporting on human rights violations (especially in politically sensitive cases), by supporting victims’ and survivors’ claims to redress, by protecting those at risk, and by holding government and other public officials to account.

~ ~ ~

The Council should not reward Burundi for its non-cooperation. It should make clear that being a Member of the Council comes with an enhanced responsibility to accept scrutiny. In the absence of measurable progress, and in light of ongoing violations and impunity, we consider that there is no basis to depart from the Council’s current approach and that Burundi’s return as a Member of the Council (for the period 2024-2026) should not lead to reconsidering the existing mandate. The Special Rapporteur remains indispensable.

Any change to the Council’s approach to the human rights situation in Burundi should be tied to measurable and sustainable progress on key human rights issues of concern, including addressing impunity for past and ongoing violations.

Until such progress is made, the Council should ensure continued monitoring and public reporting on Burundi’s human rights situation. Since the Special Rapporteur is the only independent mechanism mandated to monitor and report on human rights violations and abuses in Burundi, providing critical oversight of the situation, and as the country enters election cycles, the Council should, through a resolution adopted at its 57th session:

-

-

- Extend the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Burundi;

- Reaffirm that all States Members of the Human Rights Council shall uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights and fully cooperate with the Council and its mechanisms, and urge Burundi to be mindful of these standards;

- Urge the Government of Burundi to cooperate fully with the Special Rapporteur, including by granting him access to the country and by providing him with all the information necessary to properly fulfil his mandate; and

- Urge the Government of Burundi to constructively cooperate with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, in particular its regional office for Central Africa, and to present a timeline for the reopening of its country office in Burundi.

-

We thank you for your attention to these pressing issues and stand ready to provide your delegation with further information as required.

Sincerely,

- Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture – Burundi (ACAT-Burundi)

- AfricanDefenders (Pan-African Human Rights Defenders Network)

- Amnesty International

- Burkinabè Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CBDDH)

- Burundian Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CBDDH)

- Cabo Verdean Network of Human Rights Defenders (RECADDH)

- Central African Network of Human Rights Defenders (REDHAC)

- CIVICUS

- Coalition of Human Rights Defenders in Benin (CDDH-Bénin)

- Collectif des Avocats pour la Défense des Victimes de Crimes de Droit International Commis au Burundi (CAVIB)

- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI)

- DefendDefenders (East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project)

- Ethiopian Human Rights Defenders Center (EHRDC)

- European Network for Central Africa (EurAc)

- FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights)

- Forum pour la Conscience et le Développement (FOCODE)

- Forum pour le Renforcement de la Société Civile (FORSC)

- Geneva for Human Rights – Global Training & Policy Studies

- Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect (GCR2P)

- Hawai’i Institute for Human Rights

- Humanists International

- Human Rights Defenders Network – Sierra Leone

- Human Rights Watch

- INAMAHORO Movement

- International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI)

- International Federation of ACAT (FIACAT)

- International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

- Ivorian Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CIDDH)

- Ligue Iteka

- Media Institute for Democracy and Human Rights (IM2DH) – Togo

- Nigerien Human Rights Defenders Network (RNDDH)

- Protection International Africa

- Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

- Réseau des Citoyens Probes (RCP)

- SOS-Torture / Burundi

- Stichting Global Human Rights Defence

- Togolese Human Rights Defenders Coalition (CTDDH)

- West African Human Rights Defenders Network (ROADDH/WAHRDN)

- World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

Annex:

Risk Factors and Indicators as per the UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes (Burundi)

(list not exhaustive)

Common Risk Factors (Risk Factors 1 to 8)

Under Risk Factor 1 (Situations of armed conflict or other forms of instability (Situations that place a State under stress and generate an environment conducive to atrocity crimes)):

Indicators relating to security crisis, armed conflict in neighboring countries, political instability, political tensions, economic instability, crisis in the national economy, acute poverty, and social instability, including instability caused by exclusion or tensions based on identity issues.

Under Risk Factor 2 (Record of serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law (Past or current serious violations that have not been prevented, punished or adequately addressed)):

Indicators relating to past and present violations, past incitement to international crimes, impunity, politicization or absence of reconciliation or transitional justice processes following conflict, and widespread mistrust in State institutions.

Under Risk Factor 3 (Weakness of State structures (Circumstances that negatively affect the State’s capacity to prevent or halt atrocity crimes)):

Indicators relating to the national legal framework and institutions, lack of an independent and impartial judiciary, lack of effective civilian control of security forces, high levels of corruption, absence or inadequate external or internal mechanisms of oversight and accountability, and lack of capacity and resources for reform.

Under Risk Factor 4 (Motives or incentives (Reasons, aims or drivers that justify the use of violence against protected groups, populations or individuals)):

All indicators relating to reasons, aims or drivers that justify the use of violence, including ideologies based on the supremacy of a certain identity or on extremist versions of identity.

Under Risk Factor 5 (Capacity to commit atrocity crimes):

Indicators relating to a strong culture of obedience to authority and the presence of or links with other armed forces or with non-State armed groups.

Under Risk Factor 6 (Absence of mitigating factors (Absence of elements that, if present, could contribute to preventing or to lessening the impact of serious acts of violence against protected groups, populations or individuals)):

Indicators relating to a closed civic space, lack of international media attention, limited international cooperation, lack of incentives or willingness of parties to a conflict to engage in dialogue, make concessions and receive support from the international community, and lack of an early warning mechanism.

Under Risk Factor 7 (Enabling circumstances or preparatory action (Events or measures which provide an environment conducive to the commission of atrocity crimes, or which suggest a trajectory towards their perpetration)):

Indicators relating to the strengthening of the security apparatus, the government’s refusal to allow the presence of NGOs and other international actors, increased acts of violence, increased politicization of identity, and inflammatory rhetoric and hate speech.

Under Risk Factor 8 (Triggering factors (Events or circumstances that, even if seemingly unrelated to atrocity crimes, may seriously exacerbate existing conditions or may spark their onset)):

Indicators relating to acts of incitement or hate propaganda targeting particular groups or individuals, to armed conflicts or serious tensions in neighbouring countries, and to elections and pivotal activities related to [elections].

Risk Factors 9 to 14 are Specific and associated with Indicators pertaining to the risk of genocide,

crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Some of them might be present in Burundi (see “Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes,” op. cit. at footnote 5, pp. 18-24).

Related Content

Recommendations for the 51st Session of the Universal Periodic Review