A Tribute to Mohamed Sahnoun, 1931- 2018

New York, 30 January 2019

I have always been more than a little embarrassed, although of course also very touched, by the Global Centre’s original decision a few years ago to establish this lecture in my name. So I am more than delighted that Simon and his team should now have accepted my suggestion that the late, great Mohamed Sahnoun – colleague and friend to so many of us here, and my indispensable partner in the genesis of R2P as co-chair of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty – should now have his own contribution overtly recognised in the renaming of this lecture.

And I am particularly delighted that this lecture today is being given in the presence of Mohamed’s daughter Hania, representing his wonderfully supportive family, whom I know meant so much to him throughout his life, not least in his last years when his body, but never his mind or spirit, was failing him.

Not the least of the attractions of renaming this Lecture is that it gives visible recognition of the reality that that R2P has always been a joint North-South project. For all his total commitment to universal values and the indispensable role of the United Nations in protecting and advancing them, no one could have been a more obviously passionate son of the South than Mahomed Sahnoun, embodying in his own struggles, experiences and achievements everything the global South has been about.

Born in Algeria in 1931, the son of an imam, educated at the Sorbonne and later at New York University, he returned from Paris to serve in Algeria’s National Liberation Front in the days of its fight against French colonialism, where he was arrested and tortured, as recounted in his autobiographical novel Mémoire Blessée (“Wounded Memory”). When independence was won, he became diplomatic adviser to the country’s provisional government, and subsequently devoted his whole life to diplomacy and the pursuit of peace, with his career postings and titles enough to fill multiple lives.

His first major postings, from the mid-60s to mid-70s, were as deputy secretary general of the Organization for African Unity at its headquarters in Addis Ababa, then of the Arab League. He went on to be Algeria’s ambassador to Germany, France, the United Nations, United States and Morocco. And from the early 1990s he represented the UN in a series of senior capacities, first winning huge international respect (though unhappily not the continuing support of Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali) for the mediation skills he showed as special representative to Somalia in 1992, and then playing multiple roles in the Great Lakes, the Congo, Sudan and Namibia and elsewhere as Special Advisor to Kofi Annan – at one point in the 1990s dealing with five conflicts at once in Africa on the UN’s behalf, and for six months sleeping almost entirely on aeroplanes.

He served on the Bruntland Commission, played a key role in the ensuing Rio, Kyoto and Paris conferences and agreements, and remained a strong advocate of sustainable development. With Cornelio Sommaruga, former International President of the Red Cross, he launched the Caux Forum for Human Security, reflecting his passionate commitment to intercultural and interfaith dialogue, and he was a member of the boards, among other organizations, of the University for Peace, my own International Crisis Group, and of course the Global Centre for R2P, of which he was founding co-chair until his passing last September, at the age of 87.

Perhaps above all, apart from all his innumerable other diplomatic achievements, Mohamed will be forever remembered – certainly by me and his colleagues on the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, and many of us here today – for the absolutely crucial role he played in the birth of R2P. Working together with our Canadian Government sponsor we assembled what has been described as a ‘dream team’ of Commissioners, straddling East and West and including from the global North figures like US Congressman Lee Hamilton and Michael Ignatieff, and from the global South former Philippines President Fidel Ramos, and Cyril Ramaphosa, now South Africa’s President.

Working at breakneck pace, with eleven regional roundtables and national consultations and five full Commission meetings over less than twelve months, we produced a report in September 2001 which, in substituting the idea of ‘the responsibility to protect’ for that of ‘the right to intervene’, is now almost universally acknowledged as having been not only conceptually ground-breaking, but creating the foundations for a genuine North-South consensus on how to respond to mass atrocity crimes where none had previously existed.

In all of this Mohamed Sahnoun played an absolutely central role, and was an absolute delight to work with. All of us associated with the Commission – and who worked with him in other capacities over the years – fondly remember, Mohamed’s extraordinary capacity to bring people together, bind wound, and search out common ground. What I think we will all forever remember was Mohamed’s delightful capacity to defuse likely tensions, usually with African parables involving lions, monkeys, crocodiles, scorpions or all of the above – and to exert an appropriate leavening influence on his sometimes, I have to acknowledge, overly exuberant Antipodean colleague.

In his own obituary tribute, former UN special adviser on R2P, Ed Luck, said of Mohamed’s earlier career when he was posted as Perm Rep in New York and Ambassador in Washington, that “he was always a font of reason, balance, and optimism even in days when much of the membership was sharply divided along North-South and East-West lines. He combined a keen intellect and articulate voice with unusual humility and grace. He had a knack for listening, for valuing perspectives sincerely argued even if they did not coincide with his. He always grasped the bigger picture and more forward-looking vision.”

As we look out at the world around us today – and at the way in which, for all its overwhelmingly unquestioned acceptance now in principle, R2P has struggled to gain any traction at all in response to the catastrophes in Syria, Yemen and Myanmar in particular – the unhappy reality is that those qualities have never been more needed, but have never been in such short supply.

There were not many like Mohamed Sahnoun, and we deeply mourn his passing.

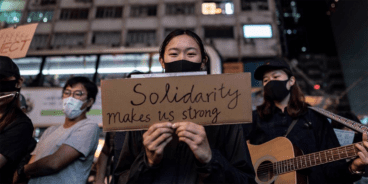

Revitalizing the Struggle for Human Rights