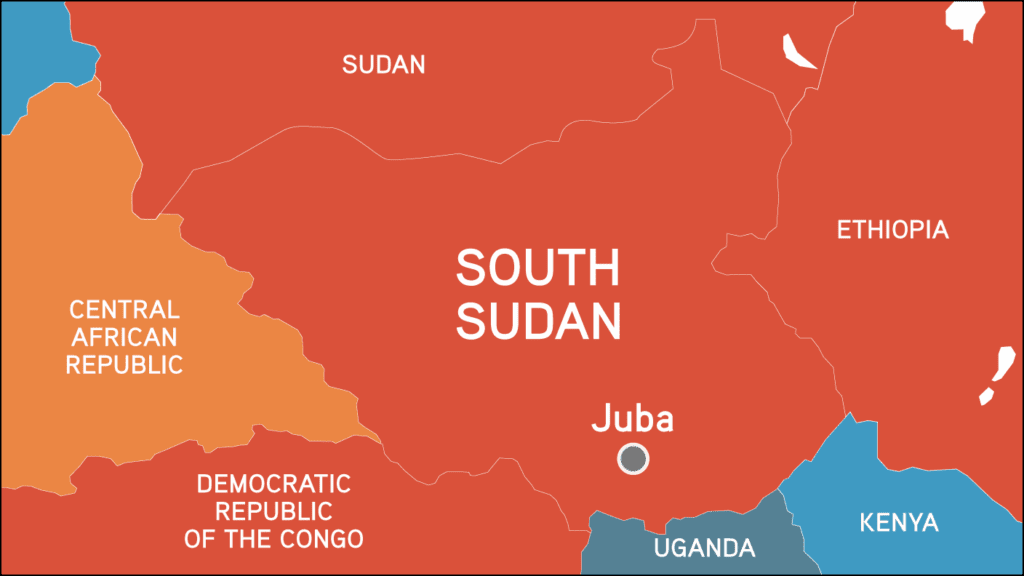

South Sudan

The potential collapse of the peace process, coupled with ongoing localized and inter-communal violence, pose a grave and escalating threat to civilians in South Sudan.

BACKGROUND:

Since gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan has experienced persistent conflict and atrocities, with successive phases of violence threatening civilians across the country. The civil war between December 2013 and August 2015 resulted in an estimated 400,000 deaths, with both the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), under the leadership of President Salva Kiir, and the SPLA-In Opposition (SPLA-IO), under the leadership of Riek Machar, perpetrating widespread atrocities, including extrajudicial killings, torture, child abductions and sexual violence.

Multiple agreements to resolve the crisis were signed between 2015 and 2018, including the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS). The R-ARCSS established the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU), placing President Kiir and First Vice President Machar in a power-sharing arrangement intended to end the civil war and establish a path toward stability. It outlined a transitional framework centered on power-sharing, institutional reform and eventual national elections. However, its implementation has been repeatedly delayed, prolonging political uncertainty and deepening mistrust among the parties. The transitional period has been extended multiple times, with the latest extension postponing the country’s first elections to December 2026 due to the lack of necessary reforms and infrastructure. Amid the stalled implementation, ongoing hate speech, grave human rights violations and abuses and localized conflict, including intermittent fighting and ethnic violence, continue to rise.

Since the start of 2025 hostilities between government forces and opposition groups, as well as inter-communal tensions have intensified, with populations enduring conflict-related violence, sexual and gender-based violence, killings and other abuses perpetrated by various forces. Risks escalated further amid renewed national conflict, particularly following the house arrest of Riek Machar and his wife, Interior Minister Angelina Teny, on 26 March. Since then, security forces loyal to President Kiir have detained at least 22 individuals, including political and military figures aligned with Machar.

Over 9.3 million people – more than two thirds of the population – need humanitarian assistance. An estimated 2.0 million people remain internally displaced and 2.29 million have fled to neighboring countries.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

Over the first eight months of 2025, ongoing violence and insecurity triggered approximately 397,000 new displacements, with the highest numbers reported in Upper Nile, Jonglei and Central Equatoria. Between April and June the Human Rights Division of the UN Mission in South Sudan documented 635 civilians killed, 676 injured, 133 abducted and 74 subjected to conflict-related sexual violence – a 204 percent increase compared to the same quarter in 2024 and the highest number of civilian victims recorded in a single quarter since 2020.

In recent months, political contestation and intense military operations, including aerial bombardments and indiscriminate attacks, have significantly increased in the Greater Upper Nile, Jonglei, and Western and Eastern Equatoria regions. These developments have resulted in substantial civilian casualties, the destruction of critical infrastructure, including health facilities, schools and public buildings, widespread displacement and the forced separation of families.

The escalation of inter-communal violence and subnational clashes has been particularly severe in Upper Nile State. On 14 February armed youth launched an attack on a market in Nasir, killing at least 21 people and displacing thousands. In retaliation, government forces reportedly deployed improvised air-dropped incendiary weapons, causing the deaths and severe burn injuries of dozens of civilians, including children, and destroying key infrastructure. Tensions further increased on 11 September when Machar was charged with treason, murder and crimes against humanity. The charges are linked to violence involving the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) and the White Army – a loosely organized militia of mostly Nuer youth believed to be aligned with Machar. Fighting between these groups intensified earlier this year and renewed on 2 September, resulting in the deaths of four SSPDF soldiers and 10 militia members.

The conflict in neighboring Sudan continues to impact South Sudan. Hundreds of thousands of refugees and returnees have been forced to flee Sudan into South Sudan, straining already limited resources and compounding existing food insecurity. Cross-border movements by armed groups on both sides have heightened insecurity, including in the disputed Abyei border region.

ANALYSIS:

The prolonged delays and ongoing friction within the TGoNU fuel local conflicts, as senior political and military leaders continue to exploit long-standing ethnic divisions to serve their own agendas. The repeated failure to uphold multiple peace agreements, continued political competition and mobilization of armed groups show a lack of genuine commitment to a political solution by South Sudan’s leaders. Tensions over access to resources and political appointments have led to violent clashes and serious human rights violations, as both parties prioritized the preservation of personal power, allowing mistrust to deepen ethnic divisions and fuel violence across the country. Delays in reforming the security sector appear to be a deliberate strategy by President Kiir to retain dominance.

The renewed clashes in Upper Nile have sparked concerns about a potential resurgence of ethnically driven violence given the area’s history of conflict. The recent violence and arrests, as well as the subsequent legal actions against Machar, have heightened political tensions in Juba and elsewhere, further straining the fragile relationship between Kiir and Machar. These developments have seriously jeopardized the viability of the R-ARCSS and have cast doubt on the existence and functionality of the TGoNU, with UN officials warning that South Sudan is on the brink of relapsing into civil war.

The continued influx and accessibility of small arms, light weapons and ammunition among armed groups, government forces, civilians and youth groups have further militarized society and made inter-communal clashes increasingly deadly. Ongoing armed conflict and continued violations of ceasefire agreements underline the importance of the UN Security Council (UNSC)-imposed arms embargo and targeted sanctions.

A pervasive culture of impunity continues to fuel resentment, recurring cycles of violence and atrocity crimes. Neither the government nor opposition groups have held perpetrators within their own ranks accountable for past or current atrocities. Despite the signing into law of the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing Act 2024 and the Compensation and Reparations Authority Act 2024, none of the transitional justice mechanisms provided for by the R-ARCSS, including the Hybrid Court, have been established or are operational.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

-

- A security crisis caused by the sudden breakdown of the power-sharing arrangement, defections and confrontations between the SSPDF and SPLM/A-IO, mobilization of armed groups along ethnic lines and the politicization of past grievances.

- Impunity for serious violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL), atrocity crimes or their incitement.

- Ongoing security vacuum amid a weakened TGoNU.

- Capacity to commit atrocity crimes, including availability of personnel, arms and ammunition.

- Escalation of local disputes and inter-communal conflicts.

-

NECESSARY ACTION:

All parties must urgently recommit to the provisions of the R-ARCSS as the foundation for peace and stability in South Sudan. To prevent further political fragmentation and escalation of violence, all stakeholders must work to restore the TGoNU in full compliance with the R-ARCSS’s terms, ensuring inclusive governance, respect for political freedoms and a return to the peace process roadmap. In the absence of a functioning TGoNU, the international community should intensify diplomatic pressure on all parties to return to the R-ARCSS and guarantee its full and unconditional implementation, including security sector reform.

The authorities must release all political leaders currently held in detention. All armed groups must immediately cease hostilities and respect IHRL and IHL to prevent further civilian harm. All parties must make every effort to stop the fighting, address the root causes of inter-communal violence and ensure the safety and security of all populations. Promoting accountability and professionalism across all security forces remains critical to preventing further violence and breaking the cycle of local and national conflict.

The UNSC must impose additional targeted sanctions on individuals who actively undermine the peace process. The African Union, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development and neighboring countries should rigorously enforce the existing arms embargo to stem the flow of weapons fueling conflict.

Atrocity Alert No. 455: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, South Sudan and Ethiopia

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 469: Nigeria, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and South Sudan

Atrocity Alert No. 467: South Sudan, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Venezuela