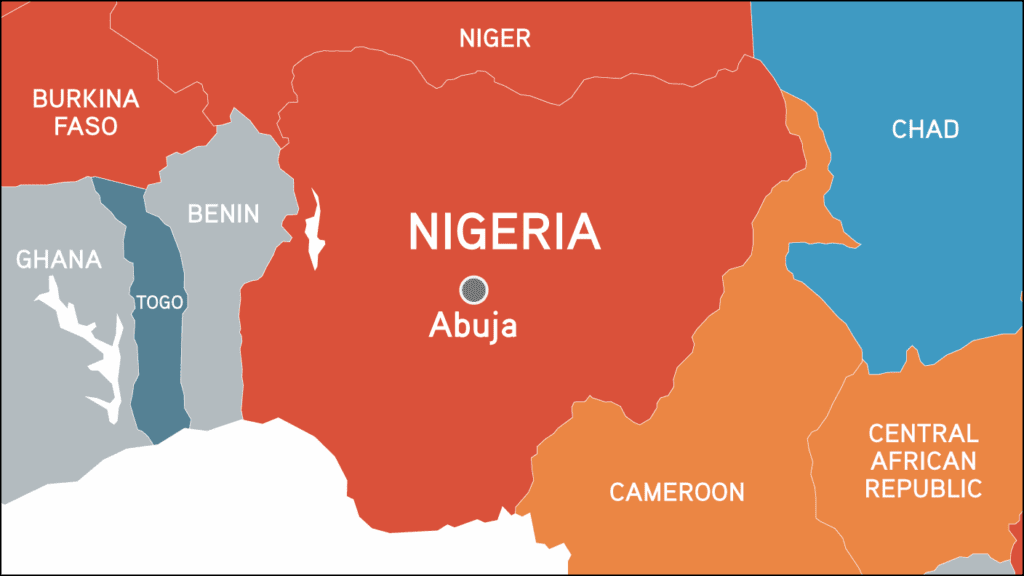

Nigeria

Escalating attacks by armed bandit groups, as well as intensified violence by Boko Haram and the so-called Islamic State in West Africa, leave civilians in Nigeria at risk of atrocity crimes.

BACKGROUND:

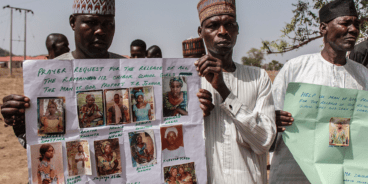

For over 15 years, civilians in Nigeria have faced multiple security threats and atrocity risks due to attacks, kidnappings and extortion by various non-state armed groups. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the security situation has resulted in a humanitarian emergency, with more than 7.8 million people – approximately 80 percent of whom are women and children – requiring urgent assistance.

Since 2011 recurrent violence between herding and farming communities over scarce resources has escalated in central and north-west Nigeria. Largely in response to these growing tensions, armed groups and gangs, including so-called “bandits,” have formed. For years such groups have perpetrated atrocities, including murder, rape, kidnapping, organized cattle-rustling and plunder. Armed bandits are also occupying vast swaths of farmland, prompting farmers to abandon their land out of fear of attack. In 2021 the government intensified its military operations in affected areas, including through indiscriminate airstrikes that have resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties.

In northern Nigeria, armed extremist groups, notably Boko Haram and splinter groups like the so-called Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), have perpetrated mass atrocities against civilians. Since Boko Haram launched an insurgency in 2009 to establish an Islamic state, tens of thousands of people have been killed and over two million displaced. Their tactics include suicide bombings, abductions, torture, rape, forced marriages, recruitment of child soldiers and attacks against government infrastructure, traditional and religious leaders and civilians. Boko Haram and allied armed bandits have recently strengthened their positions through cooperation.

Nigerian security forces have reportedly committed human rights violations during counterterrorism operations, including extrajudicial killings, rape, torture, use of excessive force and arbitrary detentions. In September 2025 the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) found Nigeria responsible for grave and systematic violations of women and girls’ rights amid ongoing mass abductions. CEDAW cited the government’s repeated failure to prevent attacks on schools or protect victims. Since 2014 more than 1,600 children have been abducted or kidnapped, and in 2024 alone at least 580 civilians, primarily women and girls, were kidnapped across several states. The actual figures are likely much higher. Survivors continue to face trauma, stigma and inadequate support.

On 11 December 2020 the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) concluded a preliminary examination into Nigeria, finding reasonable grounds to believe Boko Haram and Nigerian security forces committed war crimes and crimes against humanity.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

According to the National Human Rights Commission, at least 2,266 people were killed by bandits or insurgents during the first half of 2025 – surpassing the total number of such deaths in all of 2024. Boko Haram and ISWAP have escalated their campaigns in 2025, launching daily attacks on civilians and security forces, particularly in their stronghold regions of Yobe and Borno states. Meanwhile, Zamfara State, in northwest Nigeria, has become the epicenter of violent attacks by so-called bandits. In August gunmen killed at least two people and abducted over 100, mostly women and children. That same month, Nigerian forces killed over 100 members of a criminal gang in an air and ground raid in Zamfara.

Between 12 and 13 May ISWAP perpetrated its most sophisticated assault since launching a renewed offensive in March, attacking military installations, towns and roadways and seizing control of strategic sites in Borno. On 5 September Islamist militants killed more than 60 people, mostly civilians, alongside seven soldiers during a nighttime assault on the village of Darul Jamal, in northeastern Nigeria’s Borno State. The village had only recently seen the return of displaced residents following years of insecurity. The attack sparked a widespread military response across Borno State and has since led to an escalation in violence.

Populations in Nigeria’s north-central Plateau and Benue states are facing increased risks amid a sharp rise in inter-communal violence. More than 100 people were killed in April, including over 50 in two districts alone. Violence persisted into May and June, with at least 62 additional deaths. In Benue State, between 13 and 14 June at least 150 people were reportedly killed in an overnight assault on Yelwata village by unidentified gunmen.

ANALYSIS:

Nigeria’s armed forces have been deployed in two-thirds of the states in the country and are overstretched as Boko Haram, ISWAP and bandit groups continue to expand their areas of operation and attack all populations. Authorities are struggling to contain the escalating inter-communal violence in Benue and Plateau states. The resurgence of suicide bombings in Borno State and attacks in Yobe State have raised significant concerns about the security situation in the region. Smaller factions stemming from Boko Haram complicate the accurate identification of armed groups responsible for attacks, posing ongoing challenges to respond effectively to threats against civilians. Armed groups are increasingly using abductions to fund other crimes and control villages in the mineral-rich but poorly policed northwestern region.

Nigeria’s military has perpetrated deadly, erroneous airstrikes, raising concerns about the military’s identification of legitimate targets and disregard for civilian casualties. While the authorities have issued apologies and acknowledged responsibility, minimal steps have been taken to seek justice or accountability or to ensure military operations minimize civilian harm.

Violence between herders and farmers has increased over the past two decades as population growth has led to an expansion of the area dedicated to farming, leaving less land available for open grazing by cattle. In the Middle Belt states, competition over land use is particularly intractable as the fault lines between farmers and herders often overlap with ethnic and religious divisions. Climate change and desertification in the north has also exacerbated tensions as the loss of grazing land has driven many Fulani Muslim herders southward into areas farmed by settled communities that are predominantly Christian. While armed bandit groups are driven largely by criminal motives, many bandits are ethnic Fulani and prey on settled farming communities, exacerbating existing ethnic tensions. The Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast has compounded these challenges by driving herders into the Middle Belt.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

-

- Multiple security crises caused by a proliferation of armed groups, criminal gangs and armed extremist groups.

- Patterns of violence against civilians, or members of an identifiable group based on their ethnicity or religion, as well as their property and livelihoods.

- Climate and weather extremes causing increased competition over and exploitation of scarce resources.

- Impunity for past and ongoing atrocities by all armed actors.

- Lack of awareness or training on International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL) for military forces, irregular forces and non-state armed groups.

-

NECESSARY ACTION:

While the lack of adequate military protection for vulnerable populations needs to be urgently addressed, social initiatives and political reforms remain crucial for confronting the root causes of conflict, including poor governance, corruption, poverty – which has been exacerbated by the worst economic crisis in decades – youth unemployment, environmental degradation and climate change. Local peace commissions established to mediate inter-communal tensions and build early warning systems, such as those in Adamawa, Kaduna and Plateau states, need to be duplicated in other high-risk regions. The federal government and state authorities must develop a common strategy that addresses ongoing protection issues.

The government should utilize the Economic Community of West African States’ Early Warning System to increase police and military deployments in vulnerable areas. The government also needs to urgently reform the security sector, including by incorporating IHL and IHRL into all military and police training.

All attacks against civilians must be investigated and perpetrators of atrocity crimes and human rights violations held accountable. The Chief Prosecutor of the ICC must immediately request authorization to open a full investigation into alleged crimes committed by armed extremist groups and government security forces.

Atrocity Alert No. 444: Nigeria, Haiti and South Sudan

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 460: Nigeria, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Myanmar (Burma)

Atrocity Alert No. 459: Sudan, Ukraine and Conflict-Related Food Insecurity