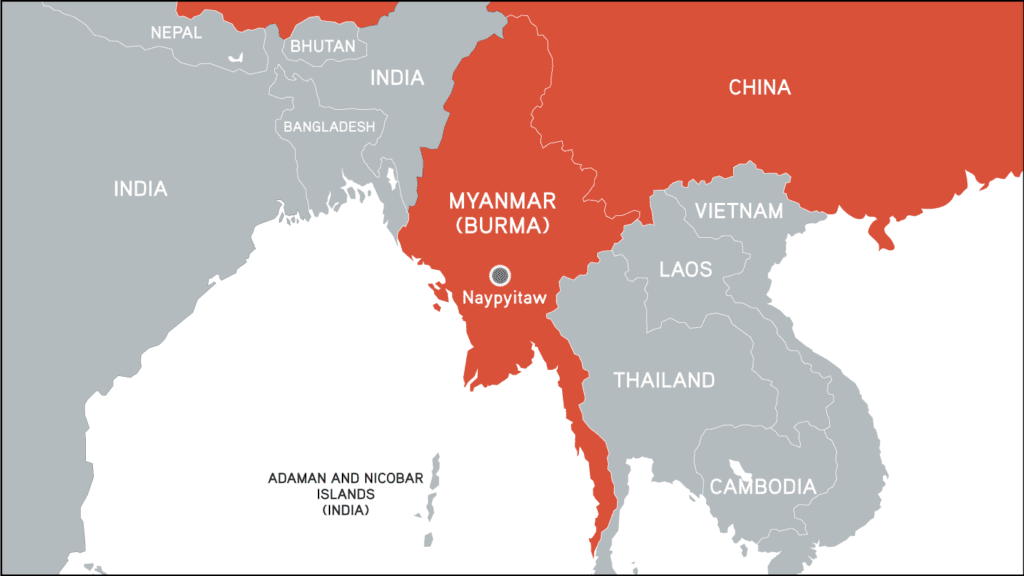

Myanmar (Burma)

Populations in Myanmar are facing crimes against humanity and war crimes perpetrated by the military and armed groups following the February 2021 coup.

BACKGROUND:

Since the February 2021 military coup and prolonged states of emergency in Myanmar (Burma), the military – known as the Tatmadaw – has perpetrated widespread violations against the population, compounding an existing human rights and humanitarian crisis in the country. The junta has relentlessly targeted civilian areas with airstrikes, scorched earth campaigns and other attacks and systematically denied or blocked humanitarian aid to civilians, particularly in the anti-military strongholds of Magway and Sagaing regions and Chin, Kachin, Shan, Kayah and Karen states. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has documented abuses against aid workers and the burning alive, dismembering, raping and beheading of civilians unable to flee attacks. Anti-junta armed groups also threaten civilians amid the escalating conflict. At least 5,938 people have been killed in attacks predominantly by the junta, while 3.4 million have been displaced and 18.6 million need assistance.

In the immediate aftermath of the coup, hundreds of thousands of people peacefully protested the re-imposition of military rule, while civilian militias – known as People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) – formed as part of an armed resistance. In retaliation, the junta has detained thousands of people accused of resisting their rule, with over 20,800 people still detained.

On 27 October 2023 a coalition of ethnic resistance organizations (EROs) launched “Operation 1027,” capturing military outposts across the country. Other groups subsequently increased attacks, including some PDFs and the Arakan Army (AA) in Rakhine State. Following months of escalating conflict, in April 2024 the junta began forcibly recruiting at least 5,000 people per month into military service.

Numerous governments have attempted to restrict the junta’s capacity to commit crimes through extensive targeted sanctions on its leaders, military-affiliated companies and others who enable their crimes, suspending development funds, imposing arms embargoes, banning dual-use goods and halting the supply of aviation fuel.

In April 2021 the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreed to a “Five-Point Consensus (5PC),” which called for a cessation of hostilities, among other steps, however there has been no progress in its implementation. In December 2022 the UN Security Council (UNSC) passed the first and only resolution on the latest crisis in Myanmar, demanding an end to the violence and calling for political prisoners to be released. The UN Human Rights Council (HRC) has adopted a resolution calling on member states to end the sale of aviation fuel to the junta.

The junta has also intentionally stoked inter-communal conflict between the ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya communities. Prior to the coup, in August 2017 the military launched so-called “clearance operations” in Rakhine State with the purported aim of confronting the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. During those operations, the majority of Myanmar’s Rohingya population were forced to flee, leaving over 900,000 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Despite ongoing risks, the junta and Bangladesh have promoted a “pilot repatriation program” for Rohingya to return to Myanmar.

In 2018 the HRC-mandated Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar concluded that senior members of the military, including General Min Aung Hlaing, should be prosecuted for genocide against the Rohingya and for crimes against humanity and war crimes in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan states. Several processes are underway to investigate and hold perpetrators accountable for crimes against the Rohingya. This includes the UN Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar, an International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation and a trial at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) initiated by The Gambia accusing Myanmar of violating its obligations under the Genocide Convention. The ICJ has allowed seven additional states to intervene in the ongoing case. Courts in Argentina, the Philippines and Türkiye have also filed cases under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

The situation across the Myanmar continues to rapidly deteriorate as the junta increasingly retaliates with air and drone strikes on civilians in areas where they have lost territory, causing significant casualties. Civilians are facing increasingly dire conditions in the northwestern areas of Chin State and Magway, Mandalay and Sagaing regions, where an estimated 1.7 million people are currently displaced – nearly half of the total number of internally displaced people in the country. Heavy fighting is also ongoing in Kayin State while sporadic violence has also taken place in Bago and Tanintharyi regions. According to the Special Advisory Council for Myanmar – an independent group of international human rights experts working to support the people of Myanmar – the junta currently holds stable control over around 14 percent of Myanmar’s territory, encompassing an estimated 33 percent of the population.

Meanwhile, conflict has impacted all but one of the Rakhine State’s 17 townships, displacing at least 570,000 people, as inter-communal tensions between ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya devolve. The AA has conducted violent raids and abuses against Rohingya civilians, perpetrating killings and enforced disappearances. On 7 November the UN Development Programme warned that 2 million people in Rakhine State are at risk of starvation as the junta’s aid and trade blockades have collapsed the economy.

On 29 October Canada, the European Union and the United Kingdom sanctioned six entities involved in providing aviation fuel or supplying restricted goods, including aircraft parts, to the junta.

On 27 November the Chief Prosecutor of the ICC filed an application for an arrest warrant against Senior General and Acting President Min Aung Hlaing, Commander-in-Chief of the Myanmar Defence Services, alleging he bears criminal responsibility for the crimes against humanity of deportation and persecution of the Rohingya.

ANALYSIS:

Impunity for past atrocities has enabled the military to continue committing widespread and systematic human rights violations and abuses against civilians, particularly those from ethnic minority populations and those who are perceived as unsupportive of the junta. Operation 1027 is the most significant challenge the junta has faced since the coup and has prompted an intensification of indiscriminate, disproportionate and targeted attacks on civilians. Some EROs have allegedly perpetrated human rights abuses, creating further protection risks. Military forces perpetrated pervasive sexual and gender-based violence during the Rohingya clearance operations and have continued this pattern of abuse against those perceived as resisting the junta. The Rohingya remain at heightened risk of recurrent atrocities, including genocide, due to the junta intentionally stoking inter-communal tensions, as well as targeting by other armed groups. Forced conscription threatens populations with further abuse, especially ethnic minority groups.

Divisions within ASEAN and the UNSC, and ASEAN’s strict commitment to the 5PC, coupled with increasing influence and support by China to the junta, have hampered the development of a coordinated international response to atrocities in Myanmar. Despite extensive targeted sanctions, fuel and arms continue to be shipped into Myanmar, including from entities based in countries imposing sanctions.

The coup, ongoing hostilities and a lack of trust complicate the prospects for the safe, dignified and voluntary repatriation of Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

- Impunity for decades of atrocities perpetrated by the military.

- History of institutionalized persecution and discrimination against ethnic minority groups.

- The military’s continued access to weapons, aviation fuel and money, providing the means to perpetrate atrocities.

- Indiscriminate attacks on civilian infrastructure while targeting anti-military strongholds.

- Increasing desperation of the junta to quell armed resistance.

NECESSARY ACTION:

The UNSC should impose a comprehensive arms embargo and targeted sanctions on Myanmar, ensure continued reporting on the crisis and refer the situation to the ICC. All UN member states, regional organizations and the UNSC should impose sanctions on Myanmar’s oil, gas and banking sectors and block the military’s access to arms and aviation fuel. Foreign companies should immediately divest and sever ties with all businesses linked to the military.

The junta should not be diplomatically recognized as the legitimate representatives of Myanmar. ASEAN member states should condemn the Tatmadaw, increasingly engage with the exiled shadow government, the National Unity Government, and revisit and/or expand upon the 5PC. International donors should utilize local humanitarian organizations for aid distribution to ensure lifesaving care and services reach those beyond junta-controlled areas.

More states should formally intervene in the ICJ case. All those responsible for atrocity crimes, including senior military leaders, should face international justice.

EROs must respect the human rights of populations in areas under their control and conduct operations in line with International Humanitarian Law.

Related Content