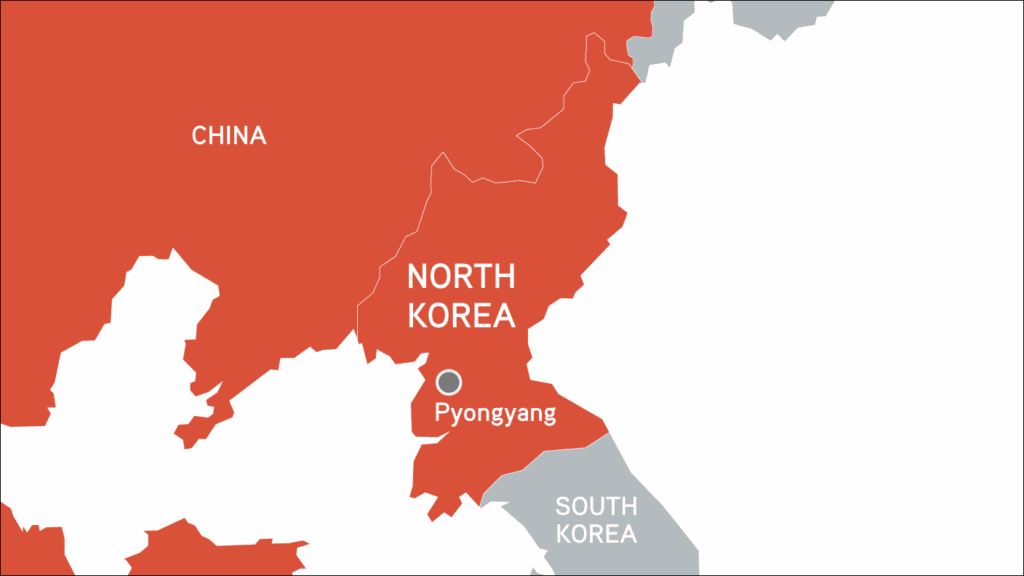

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

State authorities in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea continue to commit crimes against humanity.

BACKGROUND:

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), or North Korea, is one of the most authoritarian and repressive countries in the world, severely restricting universal human rights in a widespread manner. In a landmark report issued in February 2014, a UN Commission of Inquiry (CoI) on the DPRK established responsibility at the highest level of government for crimes against humanity.

The CoI’s report detailed harrowing abuses committed by the DPRK government, including extermination, murder, enslavement, torture, imprisonment, rape, forced abortions and other forms of sexual violence, persecution on political, religious, racial and gender grounds, forcible transfer of populations and the inhumane act of knowingly causing prolonged starvation. Detentions, executions and disappearances are characterized by centralized coordination between different parts of the extensive security system, which includes labor camps, political prisons and detention centers. The CoI reported that the government targets those considered to be “politically suspect,” including non-nationals who are labeled as “hostile.” Individuals accused of political crimes have been subject to abduction, enforced disappearance and execution without trial.

In January 2023 the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) found that serious human rights violations and possible international crimes, including abductions and enforced disappearances, overseas forced labor and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), continue to occur. The UN Secretary-General has also documented pervasive torture and forced labor among the country’s large detainee population. OHCHR concluded in July 2024 that forced labor is institutionalized in the DPRK and may constitute the crime against humanity of enslavement.

For decades the DPRK government has attempted to insulate itself from international engagement and scrutiny. The government has refused to cooperate with international human rights mechanisms and offices, including the OHCHR office in Seoul and the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the DPRK. Prolonged isolationist measures and the alleged diversion of aid have severely restricted access to food, medicine, healthcare and livelihoods.

The DPRK government further entrenched its policy of isolation by closing international borders and enforcing repressive and unnecessary restrictions on basic freedoms under the pretext of preventing the spread of COVID-19. Since the partial reopening of the DPRK’s borders on 26 August 2023, Chinese authorities have reportedly forcibly returned more than 800 people. As highlighted by the CoI, China considers border-crossers to be illegal “economic migrants” and does not allow them to seek asylum, defying its commitments under international refugee law.

In response to the CoI’s findings, in December 2014 the human rights situation in the DPRK was added as an item on the UN Security Council’s (UNSC) agenda. Prior to that, the UNSC engaged with the DPRK almost exclusively in the context of nuclear non-proliferation and had never directly addressed ongoing human rights abuses. Despite the Council holding several meetings on this agenda item, there have yet to be any tangible outcomes.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

The HRC and UN General Assembly have brought renewed attention to the human rights situation in the DPRK. On 4 September 2025 the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights published a report requested by the HRC on human rights in the DPRK, commemorating the 10th anniversary of the CoI report. The new report provides updates on the human rights situation since 2014 and reviews implementation of the CoI’s recommendations. Earlier in the year, on 20 May, the General Assembly held a high-level plenary meeting to address the human rights situation in the DPRK.

The Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team (MSMT) is a mechanism comprising 11 states, established in October 2024 following Russia’s veto of the UNSC resolution that would have renewed the mandate of the Panel of Experts (PoE) supporting the 1718 DPRK Sanctions Committee. The MSMT continues to assess compliance with DPRK-related sanctions and has issued public reports on relevant violations. Notably, in May 2025, the MSMT released a report documenting unlawful military cooperation between the DPRK and Russia, corroborating earlier PoE findings with satellite imagery and other credible evidence of prohibited transfers of goods and materiel. These developments follow the DPRK’s April acknowledgment that it deployed 11,000 troops to support Russia’s war effort in Ukraine and the June 2024 mutual defense pact signed between the two states, which pledges reciprocal military assistance.

ANALYSIS:

Despite international engagements focused on denuclearization and other security issues, the human rights and humanitarian situation in the DPRK have largely been neglected. The DPRK government’s prioritization of its illicit nuclear and missile programs over the welfare of its people reflects not only serious domestic neglect but also heightens risks to international peace and security.

The country’s human rights record is intimately linked to its weapons development program, which benefits from forced labor, and contributes to widespread poverty and hunger through unequal resource distribution. The DPRK’s role in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is underpinned by this robust forced labor system and other human rights violations, many of which amount to crimes against humanity. The DPRK government’s policy of forced military conscription, which in some instances may amount to slavery under international law, means that many North Korean soldiers may be unwittingly abetting and/or perpetrating potential war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ukraine.

The repression of civil society and independent media, as well as the absence of political space for open debate, is intended to perpetually silence criticism of the authorities and diminish opportunities for the review and reform of the DPRK’s political system and human rights practices.

The forced repatriation of refugees and asylum seekers by neighboring states has left these populations at grave risk of internment, torture, SGBV, enforced disappearance or execution. SGBV in the DPRK is not incidental but a systematic tool of state repression, embedded within broader patterns of indoctrination, discrimination and persecution against women and girls.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

-

- Authoritarian government and the absence of any checks on the power of the DPRK leadership.

- Persistent impunity for past and ongoing atrocity crimes committed by the DPRK government.

- Record of serious violations of International Human Rights Law and customary international law.

- Economic instability, poverty and famine, exacerbated by government policies.

- Significant capacity to commit atrocities, especially against detainees, women, persons with disabilities and children.

-

NECESSARY ACTION:

The DPRK authorities must allow for the return of international humanitarian organizations and guarantee rapid and unhindered access to vulnerable populations. Neighboring states have a responsibility under international law to provide safe passage out of the DPRK for civilians at risk of human rights violations and likely international crimes and should strictly adhere to the principle of non-refoulement. The Chinese government should permit the UN Refugee Agency access to all detained North Korean refugees.

The international community’s legitimate pursuit of denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula should not overshadow the need to uphold the universal human rights of all Koreans. Any negotiations on rapprochement with the DPRK should aim to address ongoing human rights violations and abuses. The DPRK government should fully cooperate with OHCHR and allow entry to the Special Rapporteur.

UNSC members should act on the recommendations made by the CoI and other relevant human rights mechanisms and offices, including by referring the situation to the International Criminal Court and imposing targeted sanctions against those responsible for or complicit in crimes against humanity, regardless of the position of the alleged perpetrator. States must ensure that all prevention and accountability efforts are grounded in a gender-sensitive lens that reflects the diverse experiences and needs of affected populations.

For more on the Global Centre’s advocacy work on the situation in DPRK, see our DPRK country advocacy page.

Atrocity Alert No. 420: Myanmar (Burma), Syria and Forced Labor

Related Content

Populations at Risk, November 2025